A Musical Up-Roar 1944-46

If an exhibitor who had been running MGM cartoons in 1935 did a Rip Van Winkle and awakened in 1945, he would have seen quire a difference in the product. The new films of the time were less cutesie-poo – in fact, such style had virtually gone away, replaced by a fast-paced, gag oriented style. MGM was able to keep up with the trends prevalent in Warner Brothers’ toons, while aided and abetted by their own Tex Avery influence, and were walking off with little gold statuettes. There was no room for a Calico Dragon, and Spring would have to spring in an entirely different way for Tom and Jerry than in the Harman-Ising days.

If an exhibitor who had been running MGM cartoons in 1935 did a Rip Van Winkle and awakened in 1945, he would have seen quire a difference in the product. The new films of the time were less cutesie-poo – in fact, such style had virtually gone away, replaced by a fast-paced, gag oriented style. MGM was able to keep up with the trends prevalent in Warner Brothers’ toons, while aided and abetted by their own Tex Avery influence, and were walking off with little gold statuettes. There was no room for a Calico Dragon, and Spring would have to spring in an entirely different way for Tom and Jerry than in the Harman-Ising days.

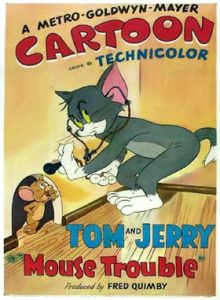

Mouse Trouble (12/23/44) – And the chase continues. Academy Award style. But this time, Tom tries to do it by the book, sending away by mail for “How To Catch a Mouse”, by Random Mouse Books. The volume is full of helpful hints – about as helpful as the Acme catalog is to Wile E. Coyote. The film is also unique for the series, in that consequences of gags early in the film continue to remain without cure through the end of the episode, leaving Tom progressively and sequentially the worse for wear – even forced to wear an ill-fitting red toupe to cover a bullet-scalping. A further consequence involves swallowing a wind-up mouse used to woo Jerry with a “Come up and see me sometime” voice track. The voice is still emitting from Tom’s gullet every time he hiccups, and by the film’s end, an explosion sends Tom, as an angel, upwards on a heavenly cloud, still inviting Jerry to “come up and see him” for the iris out. Songs: “All God’s Chillun’ Got Rhythm”, introduced by Ivie Anderson ad chorus in the Marx Brothers’ A Day at the Races. Ivie would record the piece for Variety, while Duke Ellington’s full band got it for Master. Decca issued a vocal by Judy Garland, and a band version by Jimmy Dorsey. Fletcher Henderson covered it on Vocalion. Bunny Berigan also recorded it for Victor, in some of the first recorded work for his big band. Shari Lewis would revive it for the “Hi Kids” album on Golden.

Jerky Turkey (4/7/45) – The story of the pilgrims at Plymouth Rock and of the first Thanksgiving gets the Tex Avery treatment, with an ample supply of wartime gags (including caricatures of many of the studio staff waiting in line for rationed cigarettes). A pilgrim (voiced by Bill Thompson), goes hunting for a turkey (voiced a la Jimmy Durante, and every bit as nervy as Screwball Squirrel). There is even a throwaway gag regarding Superman, as the turkey dons a super suit to let bullets bounce off his chest. The action is frequently interrupted by a slow-walking bear wearing a sandwich sign, advertising “Eat at Joe’s”. The Turkey proposes that, as the pilgrim will never catch him anyway, they might as well both eat at Joe’s. They follow the bear into the diner – but only one emerges from the doorway – the bear, picking his teeth and with a full belly, an inscription on his back now revealing “I’m Joe”. A cutaway view inside the bear’s belly reveals the disgruntled pilgrim and turkey crammed inside, with the pilgrim holding up a counter-sign, reading “Don’t eat at Joe’s.” Song: “D’ye Ken, John Peel?”, an old British hunting ballad. Recorded for the Gramophone Co. in England by Robert Radford (possibly a freelancing Robert Carr) in a very early acoustic version. A tiny record label called Pigmy Gramophone in England issued a version by Peter Hunt. Bob Crosby recorded a swing version for Decca. English Decca issued a version by Leonard Feather and Ye Olde English Swynge Band.

The Mouse Comes To Dinner (5/5/45) – Mammy Two Shoes has set out an elaborate dinner on the table, and hopes nothing happens to it. Little does she know. Tom invites a girlfriend over for dinner, and recruits Jerry as unwilling server. When Jerry trues to rebel, Tom disciplines him by making him dance atop a hot spoon over a candlestick. Lots of violent gags with sharp and pointed objects. Jerry and the girl ultimately launch the unconscious Tom like a ship into the punch bowl, where he sinks into the drink for the fade out. Songs: “Anchors Aweigh”, “You Were Meant For Me”, and two new songs from the Duke Ellington songbook. “I Got It Bad (and That Ain’t Good)” and “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore” (originally titled “Never No Lament”). The first of these two tunes was recorded by Ellington on Victor, Les Brown on Okeh, Dinah Shore on Bluebird, Bunny Berigan on Elite, Ivie Anderson on Black and White, Ella Fitzgerald on Decca (later included in “The Duke Ellington Songbook” album on Verve). Earl Hines on RCA Victor, Patti Page on Mercury, Woody Herman on Capitol, Al Hibbler on Aladdin, Cleo Laine on Parlophone, and Nina Simone on Colpix. The second number was also recorded by Ellington on Victor, the Ink Spots on Decca, Glen Gray on Decca, Pattu Page on Mercury, Jo Stafford on Columbia, Billy Eckstine on MGM, the Hampton Hawes Trio on Discovery, and Tab Hunter on Dot.

Mouse in Manhattan (7/7/45) – A virtual solo for Jerry Mouse, with Tom sound asleep. Jerry wants to see the bright lights of the big city, and writes Tom a goodbye note. He rides the hydraulic lines under a train coach to New York, and shows up at Grand Central Station. He has an encounter with New York traffic, but does get in some sightseeing (including a low-angle view along a curbside where several pretty girls stand). He takes in night life at a swank lounge, finding romance at a vacant balcony table with a bevy of place-card holders shaped like lovely dolls. He performs a graceful skating dance with the dolls atop glass tables. However, a champagne bottle launches him off the rooftop and into the bad part of town, where an alley full of cats awaits him. In his efforts to escape, he crashes through a jewelry store window, and is mistaken for a thief by the cops. He enters the subway terminal, and is almost mowed down by one of the trains. Enough is enough. Back to the sticks, and a kiss for Tom, as Jerry tears up his farewell note. Songs: a return for “Broadway Rhythm”, and the newcomer, “Manhattan Serenade”, a 1920’s concert piece which became a 1942 pop, written by Louis Alter. The original early concert version was on a 12′ Victor by the Victor Salon Orchestra directed by Nat Shilkret. A pre-vocal version was issued by Decca in the early 30’s by Fray and Braggiotti (piano duet). When the tune became a vocal revival, versions included Tommy Dorsey with Jo Stafford on Victor, Jan Savitt on Bluebird, Ray McKinley on Capitol, Harry James with Helen Forrest on Columbia, Sam Donahue on Hit, Jimmy Dorsey on Decca, and Andre Kostelanatz on Columbia Masterworks and V-Disc.

Swing Shift Cinderella (8/25/45) – Tex Avery takes on Cinderella once again. This cartoon starts off with a clever gag featuring the wolf chasing Red Riding Hood (a litte girl), until they pass a title card with the name of the picture, and little Red realizes she’s in the wrong cartoon. The wolf, however, wants to stick around and meet this dame Cinderella, dolling up as a Hollywood wolf. Cinderella (aka the Red we all know) summons her fairy godmother, who is busy drinking dry martinis, and who in the course of the story accidentally exposes her past as Miss Repulsive of 1898. She changes Red’s attire to something befitting a night club, and a pumpkin into a woody sedan. The wolf, however, gets mixed up with the amorous Fairy Godmother, stealing her wand to produce luxury transportation for himself to the night club out of a bathtub, converting it to a swanky sports car. The godmother is only able to follow by zapping an ash can into a bucking jeep. The usual night club antics between the wolf and Red accompany Red’s production number, with more sterling animation by Preston Blair. Red manages to elude the wolf, who also seems to knock out the fairy godmother, while Red makes it back home just before the pumpkin reverts to form, and just in time to catch the night bus to Red’s occupation as a welder on the evening shift. She remarks that she is happy to get rid of that wolf, until she looks around her on the bus, to find all other workers are wolves too, all reacting with a howl at her as the picture ends. Songs: “The Trolley Song”, the hit Oscar winner from Judy Garland’s “Meet Me In St. Louis”, recorded by Judy for Decca. The Pied Pipers covered it for Capitol, and the Four King Sisters for Bluebird. Vaughn Monroe also recorded it for Victor, just after the recording ban ended. Also, “Oh, Johnny, Oh, Johnny, Oh”, a 1917 pop song (appearing in the film with the modified lyric “Oh, Wolfy”). Originally recorded by the American Quartet with Billy Murray. Elizabeth Brice (a Broadway star who had recorded duets with Charles King) got Columbias rival release. Arthur Hall also performed it on vertical-cut Gennett. It received a popular comeback as performed by Orrin Tucker with vocal by Wee Bonnie Baker on Columbia. Decca issued a vocal version by the Andrews Sisters, and a dance version by Dick Robertson. Ray Herbeck and His Music With Romance issued a Vocalion side. Riley Puckett would issue a Bluebird, and the Korn Kobblers on Varsity. A British version was issued by Elsie Carlisle on Rex, and by Joe Loss on Regal Zonophone, and Jack Hylton on HMV. In the later 40‘s, a square dance version appeared by Fenton “Jonesy” Jones with Stan Erwin and his Ranch Hands on MacGregor. Bonnie Baker would re-record the piece on her own for a promotional 78 for Gallo Wine. In later years, Decca would issue a single by Crazy Otto, culled from a Polydor master Kathy Linden would revive it for a 1958 version on Felsted.

Swing Shift Cinderella (8/25/45) – Tex Avery takes on Cinderella once again. This cartoon starts off with a clever gag featuring the wolf chasing Red Riding Hood (a litte girl), until they pass a title card with the name of the picture, and little Red realizes she’s in the wrong cartoon. The wolf, however, wants to stick around and meet this dame Cinderella, dolling up as a Hollywood wolf. Cinderella (aka the Red we all know) summons her fairy godmother, who is busy drinking dry martinis, and who in the course of the story accidentally exposes her past as Miss Repulsive of 1898. She changes Red’s attire to something befitting a night club, and a pumpkin into a woody sedan. The wolf, however, gets mixed up with the amorous Fairy Godmother, stealing her wand to produce luxury transportation for himself to the night club out of a bathtub, converting it to a swanky sports car. The godmother is only able to follow by zapping an ash can into a bucking jeep. The usual night club antics between the wolf and Red accompany Red’s production number, with more sterling animation by Preston Blair. Red manages to elude the wolf, who also seems to knock out the fairy godmother, while Red makes it back home just before the pumpkin reverts to form, and just in time to catch the night bus to Red’s occupation as a welder on the evening shift. She remarks that she is happy to get rid of that wolf, until she looks around her on the bus, to find all other workers are wolves too, all reacting with a howl at her as the picture ends. Songs: “The Trolley Song”, the hit Oscar winner from Judy Garland’s “Meet Me In St. Louis”, recorded by Judy for Decca. The Pied Pipers covered it for Capitol, and the Four King Sisters for Bluebird. Vaughn Monroe also recorded it for Victor, just after the recording ban ended. Also, “Oh, Johnny, Oh, Johnny, Oh”, a 1917 pop song (appearing in the film with the modified lyric “Oh, Wolfy”). Originally recorded by the American Quartet with Billy Murray. Elizabeth Brice (a Broadway star who had recorded duets with Charles King) got Columbias rival release. Arthur Hall also performed it on vertical-cut Gennett. It received a popular comeback as performed by Orrin Tucker with vocal by Wee Bonnie Baker on Columbia. Decca issued a vocal version by the Andrews Sisters, and a dance version by Dick Robertson. Ray Herbeck and His Music With Romance issued a Vocalion side. Riley Puckett would issue a Bluebird, and the Korn Kobblers on Varsity. A British version was issued by Elsie Carlisle on Rex, and by Joe Loss on Regal Zonophone, and Jack Hylton on HMV. In the later 40‘s, a square dance version appeared by Fenton “Jonesy” Jones with Stan Erwin and his Ranch Hands on MacGregor. Bonnie Baker would re-record the piece on her own for a promotional 78 for Gallo Wine. In later years, Decca would issue a single by Crazy Otto, culled from a Polydor master Kathy Linden would revive it for a 1958 version on Felsted.

Flirty Birdy (9/22/45) – There’s Jerry Mouse in the middle again. Tom is battling a huge hawk, who is not only hungry for Jerry, but for affection. Tom sets up a rabbit-trap-type sandwich, hoping to serve himself a side of mouse with mayo. Jerry is so quick that both Tom and the hawk have to settle for a mayonnaise sandwich. Tom ultimately goes in drag as a female hawk to distract his rival, but Jerry encourages the hawk’s romantic instincts to fever pitch. The hawk’s reactions are not quite up to Tex Avery, but they get the point across. Ultimately, Tom and the hawk take up nest-tending in a picture of avian domestic bliss. Songs: a return for “You’re a Sweetheart”, and a first use of “My Blue Heaven”, a 1927 mega-hit. Victor had a dance version by Paul Whiteman, with Bing Crosby buried among a humming chorus, and also issued a million-selling vocal version by Gene Austin. A pipe organ version by Jesse Crawford was also issued on the label. Columbia gave it to Don Voorhees as a dance version, and to the Singing Sophomores for a vocal rendition. Brunswick gave it to Ken Sisson (an orchestra spun off from Ben Bernie), and a vocal version by Nick Lucas. Perfect and Pathe gave it to Willard Robison’s Orchestra. Banner, Domino, Regal and Oriole gave it to Fred Rich’s Orchestra, with two different takes issued with two different vocalists. Vaughn De Leath had a vocal record on Edison. In its prime, the song was an international hit as well, with a very young Gracie Fields having a version on HMV. A French language version appeared by Fred Gouin on Odeon. And in Germany, John Abriani’s Six performed it with a very early vocal by Al Bowlly on Homochord. The song became an evergreen almost immediately. In 1937, Jimmie Lunceford had a successful version on Decca. The song would enjoy a revival in 1956 when New Orleans rhythm and blues singer Fats Domino had a hit with it on Imperial.

Wild and Woolfy (11/3/45) – The first of the Droopy Westerns. One of the standard Western plots, with the posse charging out of a race-horse starting gate after the wolf, who’s kidnapped Red. A race track announcer brings up both “War Admiral” and “Malicious”, two well-known horses of the day, the latter a fixture of West Coast racing, with a proclivity of come-from-behind wins, while War Admiral was the second horse to with the triple crown. Droopy winds up the unexpected tag-along hero, repeating Avery tropes dating back to Egghead in “Little Red Walking Hood”. Songs: are mostly cowboy-associated songs, including a return for “Red River Valley”, and the newcomer “Texas Plains” (also titled on some recordings “Montana Plains”). Patsy Montana (real name Rubye Blevins) recorded it for the dime store labels. Gene Autry covered it, most likely on Melotone (embed below), Perfect, et al. Bill Boyd and his Cowboy Ramblers issued a buff Bluebird release. Riley Puckett performed it on later Bluebird. Leon’s Lone Star Cowboys got it for Decca (Champion?). Roy Churchill issued a 40’s version on Trilon. The Radio Rascals issued another on Linden. Shug Fisher and the Ranchmen (the leader being a small-time actor, who continued to appear as late as Petticoat Junction) sang it on Capitol Americana.

Lonesome Lenny (3/9/46) – “I used to have a friend once, but he don’t move no more” is the moan of a dimwitted dog (Tex’s fondness for Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men” provides the dog’s personality, lifted from his previous mutt Willoughby in Warner’s “Of Fox and Hounds”). Lenny’s rich owner purchases Screwy Squirrel from a pet store as Lenny’s new companion. “If you can catch me, you can have me”, challenges Screwy, and the madness begins. Screwy winds up in the same shape as all of Lenny’s past playmates – immobilized in Lenny’s pocket, and only able to hold up the usual Avery sign, “Sad ending, ain’t it.” Song: “If I Only Had a Brain”, from The Wizard of Oz. Kay Kyser would issue a popular version on Brunswick. Vincent Lopez would cover it on Bluebird. Frankie Masters got it for Vocalion. Victor Young would include it in an album set on Decca dedicated to the movie. Gray Gordon and his Tic-Toc Rhythm performed three verses on Victor. It would receive a late revival with all verses and portions that never made the final cut of the film by Michael Feinstein on “The MGM Album” (below).

NEXT: More 1946!