Fall 2024 – Week 9 in Review

Hello folks, and welcome back to Wrong Every Time. This week has seen me fully immersing myself in 2024-in-review catch-up projects, as I’ve both torn through the first major arc of Monogatari’s Off Season and begun my viewing of the Dead Dead Demons adaptation. Both have been quite enjoyable so far; Nadeko’s latest adventure served as a surprisingly touching coda to her identity-forming adventures, and Dead Dead Demons has certainly been adapted with care, even if it feels a little superfluous in its absolute loyalty to Inio Asano’s paneling. Admittedly, it must be a terrifying thing to try adapting an artist as preternaturally gifted as Asano, but it sadly feels like such an exact adaptation only reveals the animation’s inability to match the impact of Asano’s compositions. Nonetheless, the strength of the source material still makes for a compelling ride, and I’m looking forward to catching up on the year’s key films as soon as possible. In the meantime, let’s break down the films I’ve snuck in the week’s margins!

First up this week was Fool’s Paradise, a recent film written, directed by, and starring Charlie Day of It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia fame. Day plays an amnesiac mental patient who is described as mute and mentally regressed, possessing the intelligence of “a five year old or golden retriever,” as his doctor describes. Abandoned in the center of Los Angeles, he unexpectedly gains fame as “Latte Pronto,” a movie star renowned for his silent affect and tendency to stare at the camera. Alongside his aspiring publicist Lenny (Ken Jeong), Latte navigates the wild turns of Hollywood stardom with whatever grace he can muster.

It is not terribly surprising to me that Fool’s Paradise received generally negative reviews upon its release. The film frames itself as a comedy and a parody, and only infrequently succeeds in either of those pursuits. Its sendups of Hollywood staples are familiar and generally toothless (“how about them green screen action movies and celebrity marriages”), while long stretches of its running time contain few jokes, and are more just strange and quietly sad. In many ways, it reminded me of Will Ferrell’s late-stage films like Eurovision or Stranger than Fiction, which are ultimately more earnest and sentimental than barbed and snappy.

As such, I’m sure it’s no surprise either that I was very endeared by the feature. As any fan of Always Sunny knows, Charlie is the emotional heart of the series; he’s a fundamentally decent guy finding happiness in the gutter, and his friendships with Mac and Frank are earnest and meaningful. Day brings that same sense of honest vulnerability to his directorial debut, transposing Charlie Chaplin’s Tramp character to modern Hollywood, but retaining Chaplin’s expressive, wide-eyed whimsy and positive spirit. Without a voice, his character frequently becomes either observer or scenery; he is Magritte’s Son of Man, facing and reflecting the surreal landscape around him.

Meanwhile, Ken Jeong provides all the messy humanity Day’s character is reaching towards, channeling the same desperate need to be loved that made his breakout Community character so compelling. Jeong and Day collectively conjure the groveling dirtbag chemistry of Day’s Always Sunny relationships, and Fool’s Paradise is ultimately less about the eccentricities of Hollywood than the funny ways life complicates our desire for love and understanding, for someone to say “my day was brighter for your presence in it.” That sentiment is not funny or insightful, but it’s everything. Fool’s Paradise is a messy, rambling picture, but Charlie Day is striking at the only target worth seeking.

We then screened Frankenstein’s Army, a delightfully squelchy found footage feature. The film follows a Soviet reconnaissance team in the waning days of World War II, who are tasked with destroying a German sniper nest (and also cataloging the heroic escapades of Stalin’s mighty warriors, the film’s admittedly shaky justification for its found footage concept). Upon completing their mission, they receive a mysterious distress call from another Soviet unit, which takes them to a depopulated village. Eventually, they discover what happened to the villagers: they were conscripted into the experiments of a mad German scientist, who combined their bodies with whatever machinery was at hand in order to make a ramshackle army of supersoldiers.

Frankenstein’s Army’s raison d’etre is obvious: it is a showcase for horrifying mechanized amalgams, brimming with creatures who possess saw blades for hands, hooked stilts for legs, and whatever else writer-director-creature designer Richard Raaphorst could come up with. And truly, his children are a delight to experience; trapped in dank metal corridors and surrounded by squealing monstrosities, the film frequently comes across as a demented carnival ride, propelled onward by manic momentum and the perpetual question of what monster we might encounter next. Built out of practical effects and elbow grease, Frankenstein’s inventions harken back to the ‘80s glory days of beautifully sculpted exploitation theater, like a cross between Re-Animator and Tetsuo: The Iron Man. The film’s lead performances are solid, and its reflections on the messy morality of WWII’s closing days appreciated, but Frankenstein’s Army ultimately and rightfully belongs to its delightful monstrosities.

Next up was the ‘94 Street Fighter adaptation, starring our good buddy Jean-Claude Van Damme as Colonel Guile, an international peacekeeper intent on taking down the nefarious General Bison (Raul Julia). He is alternately assisted and hampered in this quest by a variety of other combatants, with Chun Li, Ken, Ryu, Zangief, Vega, and basically all of the other Street Fighter legends finding their way into this rambling action-adventure saga.

Street Fighter was apparently maligned upon release for its campy tone and disloyalty to the source material, but to be honest, my main reaction to that is “what source material?” M. Bison is a flying “psycho energy”-infused nonsense character even in the games, and Raul Julia infuses him with more charisma than should be legally possible. Whether he’s getting misty-eyed about the future of “Pax Bisonia” or offering that iconic “for me, it was Tuesday” dismissal, Julia sells Bison’s every word and gesture, turning the crumbs of the source material into one of the great screen villains. Van Damme is unfortunately not at his best in a film where he’s not facing fellow martial artists, but Street Fighter is nonetheless brimming with duals and betrayals and dramatic explosions, proving itself just as much of a camp fighting game classic as Mortal Kombat. A light and largely delightful ride.

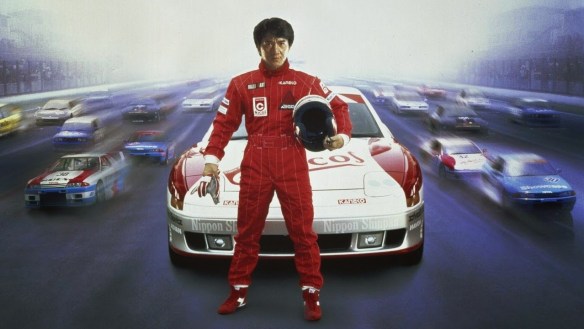

Spurred on by Tubi’s warning of their approaching unavailability, we then jumped back over to the Jackie canon with Thunderbolt, wherein Jackie Chan stars as a mechanic and former race driver who’s pulled back into the game by a nefarious street racer. The plot of this one is even less plausible than the general Jackie standard, but that’s not really the point of a film like this. More important is that the action is directed by Jackie and Sammo Hung, meaning you’re guaranteed at least one entirely unbelievable action setpiece.

In Thunderbolt’s case, there are actually two such jaw-droppers: a sequence where Jackie is tossed around his boxcar home as it’s lifted by a magnetic crane, and another where he utterly destroys a pachinko parlor while fighting off a dozen nameless goons. Both sequences dazzle and delight in their audacious improbability of design, each of them immediately prompting me to wonder what bones Jackie sacrificed in service of their fruition. And even the racing sequences are pretty darn exciting, their excellence ameliorating my natural dissatisfaction at a Jackie film climaxing in anything but a martial arts faceoff. Still not top tier Jackie, but easily recommendable for its highlights alone.