Becoming Mel Blanc

It’s a common perception among many animation fans that the nonpareil Mel Blanc simply arrived fully formed as a “cartoon voice” in the year 1937. But it’s instructive to realize just how much Blanc had already accomplished as a performer, years before his cartoon career had begun, and just how he forged his native ability into the art we still love listening to decades later. Mel was born in San Francisco’s Mission District on 30 May 1908, and he was a musically gifted youngster. Those gifts may have been at least partly genetic. His mother Eva could sing, while his father Frederick played both trumpet and piano. His older brother Henry had taught himself the piano. The family moved north when Mel was six years old. While growing up in southwest Portland, Oregon, Mel began eight years of violin lessons. Later he would add the ukulele, string bass and Sousaphone-tuba to his instrumental repertoire, and his singing voice had developed early. As cartoon director Friz Freleng once noted, “Down deep, Mel was always a musician.”

It’s a common perception among many animation fans that the nonpareil Mel Blanc simply arrived fully formed as a “cartoon voice” in the year 1937. But it’s instructive to realize just how much Blanc had already accomplished as a performer, years before his cartoon career had begun, and just how he forged his native ability into the art we still love listening to decades later. Mel was born in San Francisco’s Mission District on 30 May 1908, and he was a musically gifted youngster. Those gifts may have been at least partly genetic. His mother Eva could sing, while his father Frederick played both trumpet and piano. His older brother Henry had taught himself the piano. The family moved north when Mel was six years old. While growing up in southwest Portland, Oregon, Mel began eight years of violin lessons. Later he would add the ukulele, string bass and Sousaphone-tuba to his instrumental repertoire, and his singing voice had developed early. As cartoon director Friz Freleng once noted, “Down deep, Mel was always a musician.”

Aside from his innate ability at mastering the violin, the young Mel Blanc was something of a comic savant: he had begun practicing the many accents he heard in multi-cultural Portland, his first imitation being a thick Yiddish delivery, and he was entertaining his classmates with dialect jokes from the age of eight. As he looked back in 1976, he summed up his lifelong passion for performing, saying he’d realized, at a very early age, “I just loved to make people laugh.” As a school kid at Lincoln High, he would often skip classes to take in a vaudeville stage show, where he would watch the comedians, including big stars like W. C. Fields and Jack Benny, intently. He also listened very closely to the emerging medium of radio, the 1920s phenomenon that was displacing player pianos and family jam sessions as a home entertainment must-have. The pre-teen Blanc was already a showbiz sponge learning all he could about music, comedy and the range of the human voice.

His reputation as a classroom clown and storyteller began to precede him around town. When he had just turned fifteen in June 1923, he was featured on radio station KGW’s daily children’s show “Stories By Aunt Nell,” for which he sang several solos (accompanied by brother Henry on piano). Later that year he played a series of violin selections for the freshmen’s annual Frolics. He was given an early guest shot on KGW’s Friday night “Hoot Owls” program performing two musical numbers, including the novelty gag song parodying “Juanita” (“Wanna eat? Wanna eat, Wanita!”). Exploring all avenues of entertainment as well as honing his burgeoning talents, the young Mel even appeared in straight acting roles in plays like “Disraeli” with The Center Players. And if that wasn’t enough, he was learning comedy timing while performing in vaudeville skits, as a member of “The South Parkway Club Minstrels.”

His reputation as a classroom clown and storyteller began to precede him around town. When he had just turned fifteen in June 1923, he was featured on radio station KGW’s daily children’s show “Stories By Aunt Nell,” for which he sang several solos (accompanied by brother Henry on piano). Later that year he played a series of violin selections for the freshmen’s annual Frolics. He was given an early guest shot on KGW’s Friday night “Hoot Owls” program performing two musical numbers, including the novelty gag song parodying “Juanita” (“Wanna eat? Wanna eat, Wanita!”). Exploring all avenues of entertainment as well as honing his burgeoning talents, the young Mel even appeared in straight acting roles in plays like “Disraeli” with The Center Players. And if that wasn’t enough, he was learning comedy timing while performing in vaudeville skits, as a member of “The South Parkway Club Minstrels.”

Still in his teens, Blanc had already become so musically adept he began teaching a ukulele course while doing regular stage entertainment gigs. For these appearances he performed musical turns playing the horn, ukulele and violin, and he sang current hit songs and comical parody numbers, along with delivering dialect jokes and reciting Yiddish comic stories. In 1927, at age nineteen, he had become a regular player on Portland radio’s popular “Hoot Owls,” by now a long-established weekly charitable radio broadcast (Mel was appointed their resident comic and was dubbed “the Grand Snicker”). In the Northern California area young Mel was already a showbiz “name,” years before his animation fame. This early notoriety eventually led to his being poached, for a short time at least, by San Francisco station KFWI Radio (where his brother Henry was then the program director): here Mel was hired as a comic storyteller who played the bass tuba with the radio station’s band, the NBC Trocaderans. Unfortunately, that station went into bankruptcy soon after, a victim of the Fall 1929 stock market crash, and so Mel returned to Portland, continuing on “The Hoot Owls” and other local radio programs, where he felt right at home.

Young Mel Blanc in 1931 (at right) receives an award at the RKO Orpheum Theater. (click to enlarge)

By the time he was twenty-two, Blanc had notched up plenty of experience as a union-scale musician, including a stint as vocalist with Frank Fogelsong’s band The Bohemians. On 26 March 1931, Mel was appointed the Musical Director of the RKO Orpheum Theater, leading an eleven-piece resident orchestra (“Mel Blanc & The RKO Westerners”) that performed on stage between movies. Here he sang and played musical solos while leading the band. A review in the Oregonian newspaper was enthusiastic, with drama editor John Truebridge noting that Mel and his band “present a vaudeville act that is worthy of any circuit.” For the rest of his life, Mel Blanc proudly noted that he was recognized at the time as the youngest orchestra leader in all of the United States.

His fame was still growing in the Pacific North West and, once again, he was headhunted for San Francisco, at that time the biggest West Coast radio outlet (Hollywood didn’t begin to dominate Pacific Coast radio until the 1935-36 season). This time around, Mel was hired by the prestigious NBC network, to MC a summer variety series on station KGO. It was called “The Road Show,” debuting on 3 June 1931. Talent spotter Cecil Underwood (a future Hollywood radio producer) was most impressed by Mel’s work on KGW and offered him a job as the weekly host, where he sang dialect songs, and told comic stories. A KECA radio listing, dated 3 June 1931 in an L. A. area newspaper, noted of the premier broadcast, “a five-set vaudeville – Mel Blanc and the Milano Street Singers, with The Four Blackbirds” [the latter was an African American vocal harmony quartet, which would also be heard singing in several 1930s cartoons.]

His fame was still growing in the Pacific North West and, once again, he was headhunted for San Francisco, at that time the biggest West Coast radio outlet (Hollywood didn’t begin to dominate Pacific Coast radio until the 1935-36 season). This time around, Mel was hired by the prestigious NBC network, to MC a summer variety series on station KGO. It was called “The Road Show,” debuting on 3 June 1931. Talent spotter Cecil Underwood (a future Hollywood radio producer) was most impressed by Mel’s work on KGW and offered him a job as the weekly host, where he sang dialect songs, and told comic stories. A KECA radio listing, dated 3 June 1931 in an L. A. area newspaper, noted of the premier broadcast, “a five-set vaudeville – Mel Blanc and the Milano Street Singers, with The Four Blackbirds” [the latter was an African American vocal harmony quartet, which would also be heard singing in several 1930s cartoons.]

While working in the city where he was born, he would stay at his grandparents’ house. Mel also appeared on another NBC program “The Entertainers,” but sadly his second San Francisco gig came to an end when NBC decided to cancel “The Road Show” on 13 August at the conclusion of its summer run, rather than picking it up for a full season in the Fall and letting it gain a larger audience over time. This rather abrupt move by the network resulted in a raft of bitter and disappointed complaints to the station by fans of both Mel Blanc and the show itself.

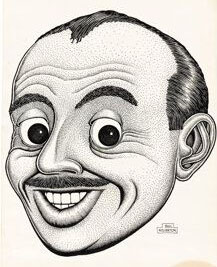

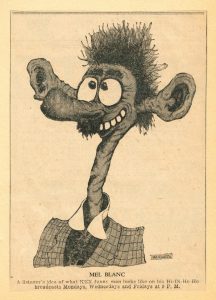

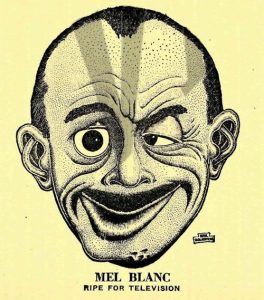

The Blanc caricatures here and below are by Blanc’s friend and fellow Portland Oregon native Basil Wolverton.

Mel finally took the plunge in March 1932, and he moved to Los Angeles. He was just twenty-three. He had saved enough money from “The Road Show” to afford a 1920 Ford convertible. He drove himself and two showbiz vaudeville pals to Los Angeles, where he resided for just over one year. During his first time as a resident in Southern California Blanc would find it tough going in Hollywood, even then a highly competitive town in a highly capricious industry. It was cutthroat show business, and the nation was then in the depths of the Great Depression. No time for buyers to spend precious bucks on unproven talent. Fortunately he knew that one of his old Portland cronies from the Milne band, a violinist named Hymie Breslau, was already in town, and they shared rent on a small apartment on Hyperion Avenue, a street already famous because Walt Disney’s renowned animation factory was located there. Cartoons, however, weren’t a concern to Mel on this first jaunt in Tinseltown.

Thanks to Cec Underwood, who had moved south to Hollywood, Mel was able to get some radio bits on NBC, and also some nibbles from the other important network, CBS, where he obtained work as a semi-regular “stooge” voice for star comedian Al Pearce. He also became one of the recurring turns on a popular KHJ comedy series “The Merrymakers”: that show, on the Don Lee radio network, was a spawning ground for several cartoon voice actors, such as Clarence Nash: the Disney crowd (including Walt) had heard Nash one night doing a crazy duck voice! And that was only weeks before Blanc had arrived in L.A.

Thanks to Cec Underwood, who had moved south to Hollywood, Mel was able to get some radio bits on NBC, and also some nibbles from the other important network, CBS, where he obtained work as a semi-regular “stooge” voice for star comedian Al Pearce. He also became one of the recurring turns on a popular KHJ comedy series “The Merrymakers”: that show, on the Don Lee radio network, was a spawning ground for several cartoon voice actors, such as Clarence Nash: the Disney crowd (including Walt) had heard Nash one night doing a crazy duck voice! And that was only weeks before Blanc had arrived in L.A.

While residing in the movie capital, Mel met and wooed Estelle Rosenbaum. They met at the Ocean Park Ballroom in Santa Monica, where Mel and his pal, Hymie, had gone to check out a band. Estelle surprised Mel by stating she had enjoyed his radio work on “The Road Show.” The young couple certainly clicked: she became his wife on 14 May 1933. Blanc would often joke in interviews that, while his first trip to Hollywood had fizzled out, “so it wasn’t a total loss, I got married!!”

With L. A. not panning out as Blanc had hoped, the young newlyweds decided to give Portland one more try: while in Los Angeles, Mel had been contacted by KEX, a powerful 5,000-watt station with enormous reach to many big cities across the country, with an offer to do his own late night comedy program, the sweetener being he would have carte blanche creative leeway: one full hour six nights a week, Monday through Saturday, from eleven to midnight! After weighing up his somewhat desperate Hollywood situation, they decided to bite the bullet.

With L. A. not panning out as Blanc had hoped, the young newlyweds decided to give Portland one more try: while in Los Angeles, Mel had been contacted by KEX, a powerful 5,000-watt station with enormous reach to many big cities across the country, with an offer to do his own late night comedy program, the sweetener being he would have carte blanche creative leeway: one full hour six nights a week, Monday through Saturday, from eleven to midnight! After weighing up his somewhat desperate Hollywood situation, they decided to bite the bullet.

Once back in Portland, and on the air, Mel and Estelle worked extremely hard for two pretty intense years, from the first show on 1 June 1933 to the final instalment on 15 June 1935. The madcap series was called “Cobwebs and Nuts,” featuring free-form comedy, crazy Spike Jones-style sound effects, much ad-libbing and an early type of DJ work, whereby Mel would spin current records and sing along in crazy accents. Each nightly hour required a lot of preparation. There were song parodies, skits on movie and radio genres like Westerns and mysteries, crazy time checks, and other gimmicks, making it sound much like a comedy show that was ahead of its time. Estelle ended up playing several recurring female roles, zany characters like the snooty Mrs. McFlogpoople IV. [Just a wild guess here, but I wonder if the posh owner of Cuddles the dog in the 1939 Porky Pig cartoon The Film Fan just might be voiced by Estelle Blanc?]

By its first year “Cobwebs and Nuts” had generated much fan mail, picked up a few sponsors and had moved to sister station KGW for even greater reach. The money the Blancs earned in this pre-actor union era totaled an underwhelming $65 a month. This wasn’t much reward for a lot of effort, even back in those Depression days. Eventually Mel took on still more radio gigs including hosting an evening talent show and doing spots on KGW’s “Sunday Morning Breakfast Club.” But, although exhausting, the experience gained was truly invaluable. Without knowing it Mel was essentially doing the same crazy voice stylings as he would do years later in the animated cartoon field. A “Variety” rave review dated 22 May 1934 opined, “[Blanc] uses only phonograph records for music, but imitates as many as 20 different characters on one program. Noteworthy are the crowds that appear faithfully each day at the studio to watch and hear him. Never a broadcast without an audience.” (Luckily, in its last year the show was reduced to a half hour nightly, which gave the Blancs at least some relief.)

By its first year “Cobwebs and Nuts” had generated much fan mail, picked up a few sponsors and had moved to sister station KGW for even greater reach. The money the Blancs earned in this pre-actor union era totaled an underwhelming $65 a month. This wasn’t much reward for a lot of effort, even back in those Depression days. Eventually Mel took on still more radio gigs including hosting an evening talent show and doing spots on KGW’s “Sunday Morning Breakfast Club.” But, although exhausting, the experience gained was truly invaluable. Without knowing it Mel was essentially doing the same crazy voice stylings as he would do years later in the animated cartoon field. A “Variety” rave review dated 22 May 1934 opined, “[Blanc] uses only phonograph records for music, but imitates as many as 20 different characters on one program. Noteworthy are the crowds that appear faithfully each day at the studio to watch and hear him. Never a broadcast without an audience.” (Luckily, in its last year the show was reduced to a half hour nightly, which gave the Blancs at least some relief.)

The mentally and physically grueling series truly gave Mel Blanc the deep comic experience that honed and forged animation’s greatest voice artist: in a “looking back” piece for the April 1946 Radio Mirror written by Mrs. Mel Blanc, she recalled her husband saying that the “Cobwebs and Nuts” program “had been his college education” in comedy and voices. (It is indeed a shame that no known recordings of this historically important series survive – by 1935 radio broadcasts were able to be air-checked on 16-inch acetate discs, so hopefully some fragments might still reside in someone’s dusty attic.)

When those two frantic years finally came to an end the Blancs were able to return to Los Angeles with heightened confidence and a solid, credible reputation, and this time Mel began working on various established shows. These included regular spots at the Warner Bros. radio station KFWB from the fall of 1935, such as “Johnny Murray’s Varieties.” Over the following year Mel was also auditioning for, and then working with, big-time comedy names of the era, like Joe Penner, Al Pearce, and his own idol Jack Benny, on coast-to-coast network programs. In mid-1936 he also became a semi-regular on KNX’s “Hollywood Barn Dance,” where he did comic routines with imitations of barnyard animals.

When those two frantic years finally came to an end the Blancs were able to return to Los Angeles with heightened confidence and a solid, credible reputation, and this time Mel began working on various established shows. These included regular spots at the Warner Bros. radio station KFWB from the fall of 1935, such as “Johnny Murray’s Varieties.” Over the following year Mel was also auditioning for, and then working with, big-time comedy names of the era, like Joe Penner, Al Pearce, and his own idol Jack Benny, on coast-to-coast network programs. In mid-1936 he also became a semi-regular on KNX’s “Hollywood Barn Dance,” where he did comic routines with imitations of barnyard animals.

Best of all, Mel Blanc’s regular contact with the Warner owned radio station, and the man he called his mentor, Johnny Murray (at that time a leading comedy-variety name in LA radio circles), would finally lead to his fabled cartoon career starting in late 1936.

It was from this lengthy mixed media training in the worlds of music, stage and radio that Blanc’s highly unusual blend of talents was now honed to a sharp edge and ready for his soon-to-start animation career. That sideroad into the world of cartoon films (aided and abetted by Warner’s sound editor Treg Brown, himself a veteran musician and band member) would quickly result in the now beloved voices of Porky Pig, Daffy Duck, Bugs Bunny, and the original voices of Woody Woodpecker for Universal and The Fox and Crow for Columbia. As Blanc’s fame in animation circles rose so did his high standing as a radio support actor. Just as Bugs Bunny began gaining huge popularity as a screen character Mel found himself working on several big coast to coast radio shows where he soon became a weekly regular: Burns & Allen, Abbott & Costello, Bob Hope and Jack Benny. The long apprenticeship in the previous two decades had paid off, because the 1940s truly belonged to Mel Blanc as an in-demand comedy stooge.

By late 1943, as the first off-screen voice artist to be contracted to a major film studio, he was on his way to obtaining name credit on international movie screens and his resultant and well-deserved show biz immortality. Still to come were the great post-war cartoon voices (Sylvester, Pepe Le Pew, Sam, Foghorn, the Martian), his later TV voices for Hanna-Barbera, his on-camera TV career with Jack Benny, and his prolific recording career with Capitol Records, but those are stories for another day.

By late 1943, as the first off-screen voice artist to be contracted to a major film studio, he was on his way to obtaining name credit on international movie screens and his resultant and well-deserved show biz immortality. Still to come were the great post-war cartoon voices (Sylvester, Pepe Le Pew, Sam, Foghorn, the Martian), his later TV voices for Hanna-Barbera, his on-camera TV career with Jack Benny, and his prolific recording career with Capitol Records, but those are stories for another day.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Information for the above was gleaned from many newspaper and radio magazine clippings in the author’s collection, Tom Reed’s audio interview with Mel Blanc (1976), John Dunning’s audio interview from 1983, various other audio interviews, Mel’s1988 autobiography “That’s Not All Folks,” the follow-up biography “Mel Blanc: The Man of a Thousand Voices” by Ben Ohmart (with input from Mel’s son Noel), radio related books like “Great Rado Personalities in Historic Photographs” by Anthony Slide, the author’s own conversations with Mel Blanc, my extensive collection of vintage radio shows and cartoons, and “The Mel Blanc Project” (2011), see https://melblancproject.wordpress.com/2011/]

©Copyright January 2025 by Keith Scott