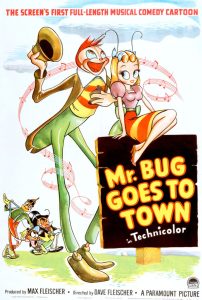

Fleischer’s “Mr. Bug Goes to Town” (1941): A Partial Animator Breakdown

Here’s a partial animator breakdown of Mr. Bug Goes to Town, Fleischer Studios’ second feature-length production! This animator breakdown will split into two separate posts; the scenes analyzed in both articles run nearly sixteen minutes of screen footage, about a quarter of the 78-minute feature.

In March 1939, just as Max and Dave Fleischer’s Miami studio progressed on their first feature-length production, Gulliver’s Travels, the subject of their second feature went into discussion. Business manager Sam Buchwald circulated a memo listing eighteen story ideas, asking the creative team to select their five favorites. Among the suggestions: an adaptation of the 1902 Broadway musical comedy King Dodo, Parade of the Wooden Soldiers (based on Victor Herbert’s production of Babes in Toyland), the story of Pandora’s Box, Johnny Gruelle’s “Raggedy Ann and Andy” stories, and a story titled “The Butterfly.”

The memo’s description for “The Butterfly” outlines an original narrative: “…The butterfly is shown as an insect, but very beautifully colored and attractive…the butterfly can be shown in very pleasant surroundings, enjoying a normal existence. Black (villain) butterflies induce her to leave and go to the big city where her beauty would be appreciated, etc., and subsequently, she gets her wings burned.”

The memo’s description for “The Butterfly” outlines an original narrative: “…The butterfly is shown as an insect, but very beautifully colored and attractive…the butterfly can be shown in very pleasant surroundings, enjoying a normal existence. Black (villain) butterflies induce her to leave and go to the big city where her beauty would be appreciated, etc., and subsequently, she gets her wings burned.”

Months later, the January 16, 1940 edition of The Film Daily announced that the Fleischers’ second feature would have “a story from Greek mythology,” which suggests that Pandora’s Box was the prominent choice.

The Miami studio opted for the screen rights of playwright/author Maurice Maeterlinck’s 1901 book The Life of the Bee. Materlinck’s detailing of bee colonies as an orderly society from an insect perspective had great potential as an animated feature, but the Fleischers couldn’t secure the rights. Despite this, Dave Fleischer seemed delighted with the idea of an insect community for the brothers’ next feature.

On March 5, 1940, Cal Howard, then working as a writer at Fleischer’s, wrote a letter to local dancer/model Hazel Murray Cornwell: “Dan Gordon just got back from N.Y. a couple days ago – he was up with Dave [Fleischer] to peddle the story to Paramount. He and Dave had left for the big city before I had returned from Cal. [California] and incidentally, the story sold, and if the War don’t throw a wet blanket over it, we will have another epic finished a year from this Thanksgiving… The title of the picture is not yet decided, but we are working under three. “The World We Live In,” “Down to Earth,” and “Trouble in Paradise”… a very cute little story all about bugs.”

On March 5, 1940, Cal Howard, then working as a writer at Fleischer’s, wrote a letter to local dancer/model Hazel Murray Cornwell: “Dan Gordon just got back from N.Y. a couple days ago – he was up with Dave [Fleischer] to peddle the story to Paramount. He and Dave had left for the big city before I had returned from Cal. [California] and incidentally, the story sold, and if the War don’t throw a wet blanket over it, we will have another epic finished a year from this Thanksgiving… The title of the picture is not yet decided, but we are working under three. “The World We Live In,” “Down to Earth,” and “Trouble in Paradise”… a very cute little story all about bugs.”

“The World We Live In” was borrowed from Josef and Karel Čapek’s 1922 Broadway stage production, The World We Live In (or Pictures from the Insects’ Life). The Čapek brothers’ satirical play portrayed insects with human characteristics, seen through the dreams of a tramp asleep in the woods. By April 1940, film trades announced that Fleischer’s plans for “Pandora’s Box” were scrapped, with the temporarily titled “Down to Earth” as their next feature-length film; the trade blurb did not mention bugs.

The Film Daily announced in July 1940 that the Fleischers had hired songwriting duo Hoagy Carmichael and Frank Loesser for their second feature. With the final written scenario completed in October, pencil animation soon followed by mid-November. Paramount approved the final script in December, expecting the Fleischer brothers to finish their new feature by next November.

The Film Daily announced in July 1940 that the Fleischers had hired songwriting duo Hoagy Carmichael and Frank Loesser for their second feature. With the final written scenario completed in October, pencil animation soon followed by mid-November. Paramount approved the final script in December, expecting the Fleischer brothers to finish their new feature by next November.

Later, on February 5, 1941, while pencil animation was still underway, key animator Al Eugster wrote in his diary that the feature’s title was now called Mr. Bug Goes to Town, suggesting Frank Capra’s Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936). The next day, The Film Daily reported that the Miami studio had started work on an animated movie to be “neither fantasy nor fable, but an original based on the fight for life by a community of insects.” Indeed, Mr. Bug was the first American animated feature with an entirely original story, not based on a past literary work.

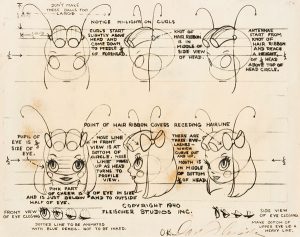

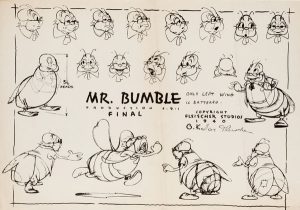

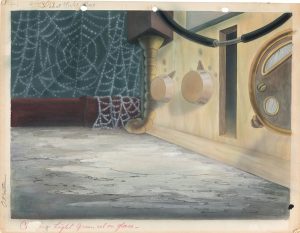

In a weedy patch of land mere inches from Broadway, Mr. Bug’s tiny insect residents live in the Lowlands, located outside the garden of a bungalow belonging to husband and wife Dick and Mary Dickens. Old Mr. Bumble the bumblebee (Jack Mercer) and his young daughter Honey (Fleischer artist Pauline Loth) run the Honey Shop and prepare for the arrival of Hoppity the grasshopper (Stan Freed), a reputable and favored young citizen of the Lowlands. Their habitat faces constant danger from “the human ones” that walk through the broken-down rod iron fence that allows them to trample on the insect houses. When a discarded lit match burns down the home of Mrs. Ladybug, the distressed populace fears the worst.

In a weedy patch of land mere inches from Broadway, Mr. Bug’s tiny insect residents live in the Lowlands, located outside the garden of a bungalow belonging to husband and wife Dick and Mary Dickens. Old Mr. Bumble the bumblebee (Jack Mercer) and his young daughter Honey (Fleischer artist Pauline Loth) run the Honey Shop and prepare for the arrival of Hoppity the grasshopper (Stan Freed), a reputable and favored young citizen of the Lowlands. Their habitat faces constant danger from “the human ones” that walk through the broken-down rod iron fence that allows them to trample on the insect houses. When a discarded lit match burns down the home of Mrs. Ladybug, the distressed populace fears the worst.

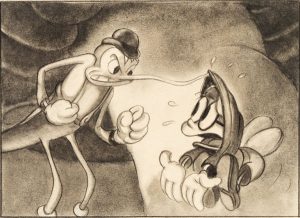

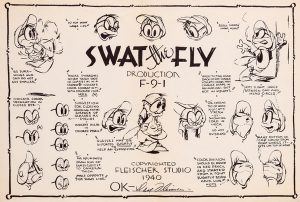

The terrible news is delivered to ruthless property magnate C. Bagley Beetle (Tedd Pierce) by his two henchmen, Smack the Mosquito (Carl “Mike” Meyer) and Swat the Fly (Jack Mercer). Beetle uses the tragedy of Mrs. Ladybug’s house to ask Mr. Bumble for his daughter’s hand in marriage in exchange for their safety at his estate where no humans disturb; Bumble refuses, and Beetle seeks revenge by rolling a discarded cigar butt to demolish the Honey Shop. The heroic Hoppity extinguishes the cigar and saves Mr. Bumble and Honey’s family business. With Beetle’s plans foiled, he calls Swat and Smack to eliminate his romantic rival, which leads to the sequence discussed in this post. James (Shamus) Culhane, once an animator for Max Fleischer in the early 1930s, directed the opening sequence of Mr. Bug, establishing the principal insect cast and their ongoing conflict with the outside human world. By then, Culhane used his Disney training to instill their animation methods in his unit.

The terrible news is delivered to ruthless property magnate C. Bagley Beetle (Tedd Pierce) by his two henchmen, Smack the Mosquito (Carl “Mike” Meyer) and Swat the Fly (Jack Mercer). Beetle uses the tragedy of Mrs. Ladybug’s house to ask Mr. Bumble for his daughter’s hand in marriage in exchange for their safety at his estate where no humans disturb; Bumble refuses, and Beetle seeks revenge by rolling a discarded cigar butt to demolish the Honey Shop. The heroic Hoppity extinguishes the cigar and saves Mr. Bumble and Honey’s family business. With Beetle’s plans foiled, he calls Swat and Smack to eliminate his romantic rival, which leads to the sequence discussed in this post. James (Shamus) Culhane, once an animator for Max Fleischer in the early 1930s, directed the opening sequence of Mr. Bug, establishing the principal insect cast and their ongoing conflict with the outside human world. By then, Culhane used his Disney training to instill their animation methods in his unit.

Tom Johnson

For his section on Mr. Bug, Johnson (or perhaps management) chose animators who could efficiently produce high amounts of footage: Al Eugster (1909-1997), Harold Walker (1904-1994), Frank Endres (1911-1995), and George Germanetti (1908-1967). While Harold Walker and Frank Endres were regulars in the Johnson unit, Eugster was a new addition. Formerly in the Culhane unit in Miami, Al contacted Sam Buchwald in California to request a place in the Johnson unit after a job offer at MGM’s cartoon studio failed to materialize. Germanetti was another recruit in Tom Johnson’s crew, known for his speed in delivering abundant footage. (Two of Johnson’s animators, Ben Solomon and Jack Ozark, didn’t animate any scenes in Mr. Bug and worked on the shorts instead.)

For his section on Mr. Bug, Johnson (or perhaps management) chose animators who could efficiently produce high amounts of footage: Al Eugster (1909-1997), Harold Walker (1904-1994), Frank Endres (1911-1995), and George Germanetti (1908-1967). While Harold Walker and Frank Endres were regulars in the Johnson unit, Eugster was a new addition. Formerly in the Culhane unit in Miami, Al contacted Sam Buchwald in California to request a place in the Johnson unit after a job offer at MGM’s cartoon studio failed to materialize. Germanetti was another recruit in Tom Johnson’s crew, known for his speed in delivering abundant footage. (Two of Johnson’s animators, Ben Solomon and Jack Ozark, didn’t animate any scenes in Mr. Bug and worked on the shorts instead.)

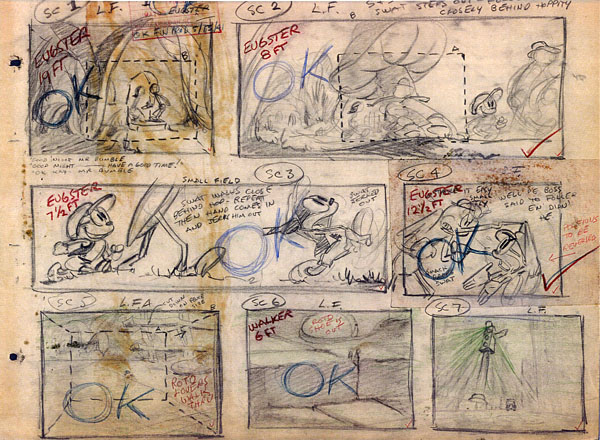

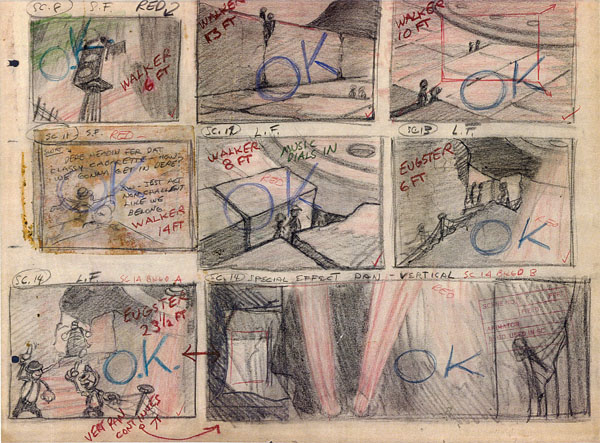

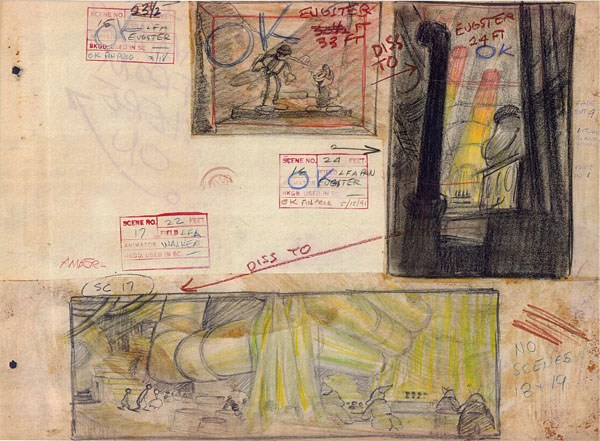

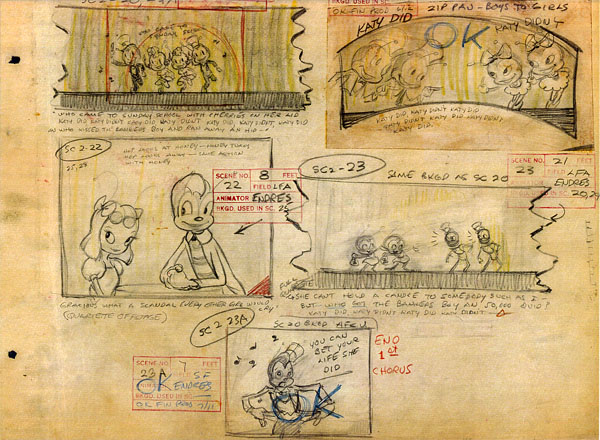

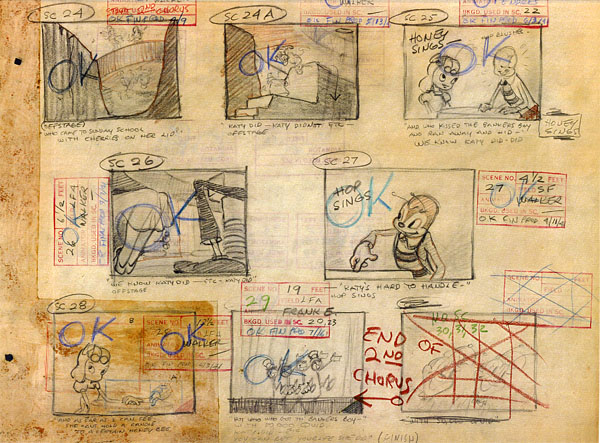

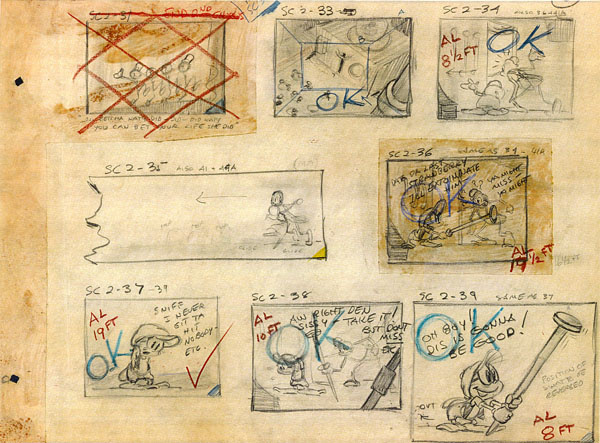

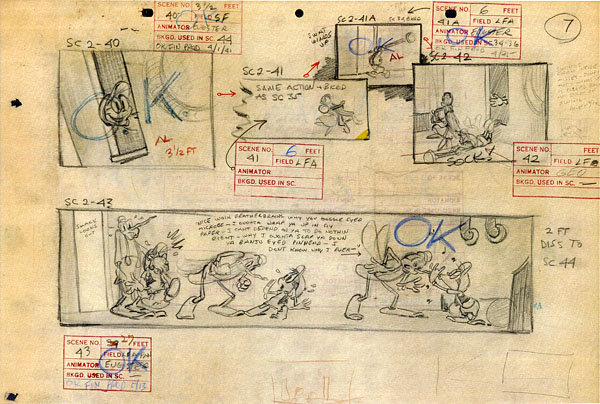

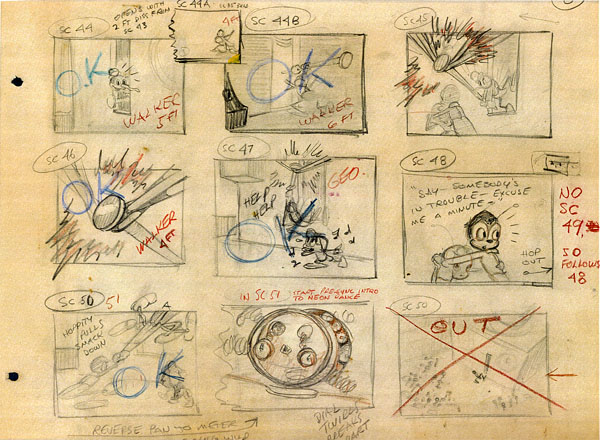

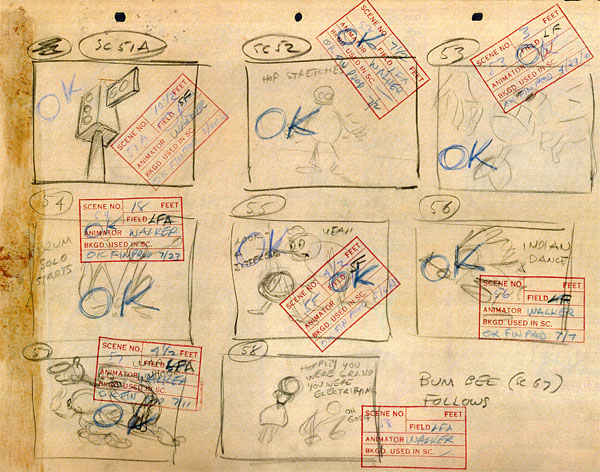

The working copy of the storyboard for Tom Johnson’s unit contains Johnson’s thumbnail drawings, which reflect the production storyboard drawn in a different size. The director boards also demonstrate how Fleischer’s head animators planned and kept track of the animator assignments, footage, music tempo, and status of their sections. Johnson’s working copy, too, reveals that the clean-up pencil animation was approved for ink-and-paint as early as March 18, 1941, with its last scenes accepted as late as July 31.

Meanwhile, between March and July 1941, the bitter acrimony between Max and Dave Fleischer, onset by Dave’s uncouth behavior intertwined with their personal and business lives, irreversibly affected their partnership of more than twenty years. As their distributor, Paramount gave out weekly advances to finance cartoon production, but the decline of the Fleischer product in the 1940-41 season deterred the brothers’ expected royalties. On May 19, 1941, Max and Dave renewed their contract with Paramount, which advanced more funds for the completion of Mr. Bug, in addition to twelve shorts featuring Popeye the Sailor and a new series of twelve Superman cartoons. At the same time, Paramount purchased all the assets of Fleischer Studios. A new agreement was signed on May 24, stipulating that Max and Dave surrender their shares of stock and that Paramount would own the Fleischer Studios name entirely—the two brothers were now under Paramount’s employ for twenty-six weeks to finish Mr. Bug.

Meanwhile, between March and July 1941, the bitter acrimony between Max and Dave Fleischer, onset by Dave’s uncouth behavior intertwined with their personal and business lives, irreversibly affected their partnership of more than twenty years. As their distributor, Paramount gave out weekly advances to finance cartoon production, but the decline of the Fleischer product in the 1940-41 season deterred the brothers’ expected royalties. On May 19, 1941, Max and Dave renewed their contract with Paramount, which advanced more funds for the completion of Mr. Bug, in addition to twelve shorts featuring Popeye the Sailor and a new series of twelve Superman cartoons. At the same time, Paramount purchased all the assets of Fleischer Studios. A new agreement was signed on May 24, stipulating that Max and Dave surrender their shares of stock and that Paramount would own the Fleischer Studios name entirely—the two brothers were now under Paramount’s employ for twenty-six weeks to finish Mr. Bug.

Later, in August 1941, composer Leigh Harline — hot off the success of an Academy Award for “When You Wish Upon a Star” in Disney’s Pinocchio — traveled to Miami to confer with Max and Dave regarding the film’s musical score. On November 3, after a month of preparation, Harline completed his background music in Hollywood. Back in Miami, Paramount requested Dave’s resignation in response to a brusque telegram Max had sent stating he could no longer work with his brother, severing the brothers’ joint agreement to continue working at the studio. Dave resigned on November 22, 1941, two days before the expiration date of the 26 weeks. Paramount appointed Sam Buchwald, Izzy Sparber, and Max’s son-in-law, Seymour Kneitel, as the new production supervisors.

Slated for a Christmas 1941 release, Mr. Bug Goes to Town was unveiled at a press screening on December 4. Though well-received by critics, theater exhibitors rejected it. Three days later, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor signaled America’s entrance into World War II—Paramount canceled the Christmas release. Three weeks later, on January 6, 1942, Paramount’s president, Barney Balaban, accepted Max Fleischer’s resignation.

Slated for a Christmas 1941 release, Mr. Bug Goes to Town was unveiled at a press screening on December 4. Though well-received by critics, theater exhibitors rejected it. Three days later, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor signaled America’s entrance into World War II—Paramount canceled the Christmas release. Three weeks later, on January 6, 1942, Paramount’s president, Barney Balaban, accepted Max Fleischer’s resignation.

Paramount released Mr. Bug in the UK, premiering in London’s Carlton Theater on January 23, under Hoppity Goes to Town. (In its 1946 American re-release, Mr. Bug was changed to Hoppity. National Telefilm Associates [NTA] acquired the film in 1958 as Hoppity, where it gained renewed popularity as a staple on local television stations.)

Finally, Mr. Bug made its commercial American debut at the Paramount Theater in Los Angeles on February 13, 1942, as part of a double bill with Preston Sturges’ Sullivan’s Travels. The following week, on February 20, Mr. Bug reached its New York City premiere at the Loew’s State Theater. Each venue only ran the film for a single week. Al Eugster noted in his diary on March 9, after viewing the film at the Olympia Theater in Miami: “Too long. Hard to follow.”

Three months later, on May 21, 1942, the Fleischer studio officially dissolved and now operated as Famous Studios, named after Paramount’s music publishing division.

Mr. Bug: The Nightclub Sequence

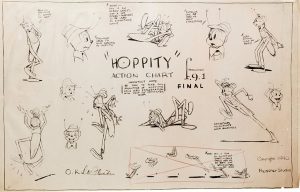

Since Al Eugster was already an experienced Disney animator, Tom Johnson gave Al the close-up personality scenes of Mr. Bug’s cast throughout the nightclub sequence. Eugster handles many scenes with Swat and Smack in this section; comparatively, Harold Walker was assigned the wider shots at the start of this section, along with ancillary footage of the traffic lights, Hoppity and Honey, and Swat and Smack traveling through the cracks in the pavement to enter the underground nightclub.

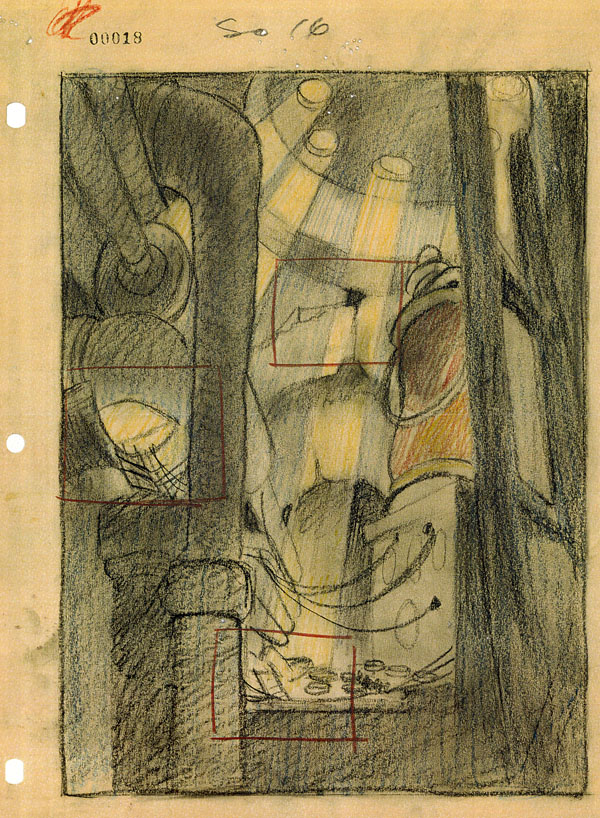

Al Eugster also animated the smaller characters in scene 16 as the camera moves downward in a vertical pan. Despite the difficulties in animating tiny characters, the amount of footage reflected highly on an animator’s quota in the production report.

This full-sized animation paper rendering for scene 16 is possibly one of the actual production storyboard drawings.

Frank Endres predominantly animates the “Katy Did, Katy Didn’t” song number, sung by Tommy Gleason and His Royal Guards, a popular radio sextet; the group received credit as “The Royal Guards” in the film.

Hoppity’s and Honey’s dance is credited to George Germanetti in the video, based on his work in scene 42. To minimize production costs, Tom Johnson (or possibly Dave Fleischer) chose to reuse the dance animation from scene 35 while intercutting between Swat and Smack’s attempts to “extoiminate” Hoppity.

Johnson’s working copy leaves the animators assigned to scenes 45, 48, 50, and 51 blank. Harold Walker seems a likely candidate for scene 45 since he animated the scenes before and after. Frank Endres handles scene 48 of Hoppity reacting off-screen and excusing himself to rescue Smack from a live wire. Most likely, Harold Walker animated scenes 50 and 51 as well.

Johnson assigned Harold Walker with Hoppity’s “electrifying” neon jitterbug dance—one of the true highlights of the whole feature.

Special acknowledgement goes to Mark Kausler, who provided the director’s board. Thanks to Jerry Beck, Bob Jaques, Mike Barrier, and Mark Mayerson for additional information and materials on this post.