Cartoons at Bat (Part 5)

Several double-headers on the schedule today – two games for Popeye, and two games for Bugs Bunny. Among the other regulation games is a somewhat wild yet plotwise-limited outing by Tex Avery, and the first appearance of baseball in feature-length animation – though really set forth in a high-budgeted “short” contained within a Disney package film.

Ration Fer the Duration (Paramount/Famous, Popeye, 5/28/43 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – Popeye, just planting his own garden of spinach in every available square inch of his property, inspires his nephews into planting a victory garden, by telling them a bit of the story of Jack and the Beanstalk, enticing them with the notion of the giant living in the clouds. They get busy, and Popeye takes a time out to doze beneath a tree. The scene moves into his dream cloud, where he imagines his nephews awakening him, to display a beanstalk of the fabled proportions sprouted up from their garden. The nephews tell Popeye to climb it, insisting “We want a giant.” Popeye claims there ain’t no giants – and just to prove it, agrees to climb the beanstalk and not bring a giant back. In fact, he uses a more modern means of transportation, producing from nowhere a motor scooter, and riding the maze of beanstalk vines like a cloverleaf freeway maze up to the top. He emerges from a manhole cover in one of the clouds, and sees upon the next-closest cloudbank a huge castle, with sign outside advertising a bed available for the swing shift. In one of the film’s more memorable gags, a taxi, entirely made of puffy white cloud, pulls up, offering transportation to the giant’s house. Popeye enters the cab for the short excursion, then asks the unseen driver, “Fare?” Misinterpreting the word as “Fair”, the driver responds. “Nope. Cloudy and rain”, as the entire taxi dissolves in a scattering of raindrops upon the world below.

Ration Fer the Duration (Paramount/Famous, Popeye, 5/28/43 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – Popeye, just planting his own garden of spinach in every available square inch of his property, inspires his nephews into planting a victory garden, by telling them a bit of the story of Jack and the Beanstalk, enticing them with the notion of the giant living in the clouds. They get busy, and Popeye takes a time out to doze beneath a tree. The scene moves into his dream cloud, where he imagines his nephews awakening him, to display a beanstalk of the fabled proportions sprouted up from their garden. The nephews tell Popeye to climb it, insisting “We want a giant.” Popeye claims there ain’t no giants – and just to prove it, agrees to climb the beanstalk and not bring a giant back. In fact, he uses a more modern means of transportation, producing from nowhere a motor scooter, and riding the maze of beanstalk vines like a cloverleaf freeway maze up to the top. He emerges from a manhole cover in one of the clouds, and sees upon the next-closest cloudbank a huge castle, with sign outside advertising a bed available for the swing shift. In one of the film’s more memorable gags, a taxi, entirely made of puffy white cloud, pulls up, offering transportation to the giant’s house. Popeye enters the cab for the short excursion, then asks the unseen driver, “Fare?” Misinterpreting the word as “Fair”, the driver responds. “Nope. Cloudy and rain”, as the entire taxi dissolves in a scattering of raindrops upon the world below.

Popeye knocks on the giant’s door, which opens to reveal the told-of giant, so tall he doesn’t even see Popeye. The massive man carries a large club over his shoulder, in the same manner that a baseball player might carry a bat, and on his chest is written the words “N.Y. Giants”. After a pause to let the joke settle in, the giant looks down at his own shirt, and in self-effacing tones mirroring casual reads in Tex Avery cartoons, remarks to the audience, “I didn’t think it was funny, either”, and wipes the lettering from his chest. The giant turns out to be a hoarder of rationed goods, including first-class rubber tires laid by his magic hen instead of eggs, sugar, silk stockings, pant cuffs, butter, gasoline, etc. “Uncle Sam could use all that stuff” says Popeye. Eventually getting the giant to sneeze with his nose full of pepper, Popeye rides a carpet bag full of the rationed goods out the door on the force of the sneeze, and falls over and over down toward earth. But his spinning is back in the real world, where the nephews are attempting to awaken him, to show off their real victory garden. Instead of beans, they have planted mutant plants that are their own solution to the rationing problem – each producing a rationed item right off the vine. POT-tatoes, CAN-taloupes, and Pine-NIPPLES are among the crops, together with “Squashes” (used tires), “Peaches” (brand new tires), and last of all, a “SHOE tree”, growing rubber-soled shoes by the dozens. Popeye laughs with pleasure at their patriotic breakthrough, as the film irises out.

Popeye knocks on the giant’s door, which opens to reveal the told-of giant, so tall he doesn’t even see Popeye. The massive man carries a large club over his shoulder, in the same manner that a baseball player might carry a bat, and on his chest is written the words “N.Y. Giants”. After a pause to let the joke settle in, the giant looks down at his own shirt, and in self-effacing tones mirroring casual reads in Tex Avery cartoons, remarks to the audience, “I didn’t think it was funny, either”, and wipes the lettering from his chest. The giant turns out to be a hoarder of rationed goods, including first-class rubber tires laid by his magic hen instead of eggs, sugar, silk stockings, pant cuffs, butter, gasoline, etc. “Uncle Sam could use all that stuff” says Popeye. Eventually getting the giant to sneeze with his nose full of pepper, Popeye rides a carpet bag full of the rationed goods out the door on the force of the sneeze, and falls over and over down toward earth. But his spinning is back in the real world, where the nephews are attempting to awaken him, to show off their real victory garden. Instead of beans, they have planted mutant plants that are their own solution to the rationing problem – each producing a rationed item right off the vine. POT-tatoes, CAN-taloupes, and Pine-NIPPLES are among the crops, together with “Squashes” (used tires), “Peaches” (brand new tires), and last of all, a “SHOE tree”, growing rubber-soled shoes by the dozens. Popeye laughs with pleasure at their patriotic breakthrough, as the film irises out.

• See RATION FER THE DURATION on DailyMotion HERE.

Happy Birthdaze (Famous/Paramount, Popeye, 7/16/43 – Dan Gordon, dir,) – Popeye receives a V-Mail letter at his battleship, in which Olive invites him to her apartment home for a cake and party in celebration of his birthday. Popeye, however, encounters a fellow crewmate he has not met before – a little runt with goggle-eyed glasses named Shorty, who has no friends and no one to send him mail, and seems intent upon doing himself in, repeatedly pulling out a pistol to aim at his own head. Popeye tries to cheer him up, with words to convince him he is as handsome as a movie star – but the name blurts out “Bob Hope” – causing Shorty to revert to the pistol again – until Popeye changes the name to “Bing Crosby”. Shorty gets invited to come along to Olive’s party – a mistake, indeed, for the talkative little busybody wants to be a part of everything, including baking Popeye’s cake. In washing up before beginning the baking, Shorty leaves the water running to flood level in the bathroom, washing Popeye out into the street and down the gutter. Shorty meanwhile gathers cake ingredients for Olive, piling them too high, and transferring the load to Popeye while Shorty retrieves a dozen eggs. A badly-timed entrance through a swinging door, and poor Popeye is toppled, with the entire mess dumped all over his uniform. Olive insists he take a bath, and Shorty runs the water again – flooding Popeye out into the sewer for a second time.

Happy Birthdaze (Famous/Paramount, Popeye, 7/16/43 – Dan Gordon, dir,) – Popeye receives a V-Mail letter at his battleship, in which Olive invites him to her apartment home for a cake and party in celebration of his birthday. Popeye, however, encounters a fellow crewmate he has not met before – a little runt with goggle-eyed glasses named Shorty, who has no friends and no one to send him mail, and seems intent upon doing himself in, repeatedly pulling out a pistol to aim at his own head. Popeye tries to cheer him up, with words to convince him he is as handsome as a movie star – but the name blurts out “Bob Hope” – causing Shorty to revert to the pistol again – until Popeye changes the name to “Bing Crosby”. Shorty gets invited to come along to Olive’s party – a mistake, indeed, for the talkative little busybody wants to be a part of everything, including baking Popeye’s cake. In washing up before beginning the baking, Shorty leaves the water running to flood level in the bathroom, washing Popeye out into the street and down the gutter. Shorty meanwhile gathers cake ingredients for Olive, piling them too high, and transferring the load to Popeye while Shorty retrieves a dozen eggs. A badly-timed entrance through a swinging door, and poor Popeye is toppled, with the entire mess dumped all over his uniform. Olive insists he take a bath, and Shorty runs the water again – flooding Popeye out into the sewer for a second time.

Shorty is starting to feel suicidal again, realizing that because of him, Popeye isn’t having any fun – not playing games and stuff as he should on his birthday. Popeye re-enters the apartment, carrying a baseball bat, intending to have some vengeance upon Shorty for his interference. Shorty sees this as an invitation for some indoor baseball, and retrieves a ball. In demonstrating the techniques of Babe Ruth to Popeye in the next room, we hear the clout of wood against ball, and watch Popeye re-enter the room, with the ball repeatedly bouncing off his head. Popeye collapses back into the adjoining room upon a square throw rug, and Shorty darts around its corners, sliding under the rug and upsetting the prone Popeye, as Shorty touhes a furnace grating that serves as home plate. Next. Shorty grabs up a golf club and ball, and demonstrates a Bobby Jones drive, which bounces repeatedly off walls in front of and behinf Popeye, rebounding between wall and Popeye’s head. Popeye falls on his back with mouth open, the ball resting upon his chest, as the pole of a souvenir pennant from Coney Island drops into Popeye’s mouth. Removing the flag, Shorty steps onto Popeye’s chest. “On the green in 1 – now for a birdie”, says Shorty, as he putts the golf ball down Popeye’s throat. Then, indoor ice hockey, with Popeye nearly swallowing the puck. The puck lands between his feet, as Shorty charges. Popeye takes aim with his hockey stick – not at the puck, but at the oncoming Shorty. He takes a wild swing, but misses, causing his skates to spin in a circle, and carve a hole in the wood of the floor. Popeye falls through, but rises again atop the floorboard, which rests as a ceiling atop the head of a gentlemanly British character who lives in the apartment below. The Britisher politely inquires what is going on, then equally-politely apologizes that he must leave, as he is losing his footing. The Britisher falls out of our view, but Popeye leaps off his head just in time, and kicks Shorty down the hole. Enter Olive with the completed birthday cake, as Popeye tries to hide the hole from view with the throw rug. Olive steps directly upon the rug, and falls through, while the cake, slightly wider in diameter than the hole, remains in the room on the floor. Popeye, realizing Olive is in trouble, darts down to the Britisher’s apartment. “She went thata-way”, the Britisher says, pointing to an Olive-shaped hole in his own floor. Popeye runs down four or five more flights to the basement, just as the silhouette of Olive appears with a clang among the basement furnace pipes. Popeye darts into the furnace, but is told by Olive that he and Shorty should never darken her door again. Olive exits, blackened with coal dust. Inside the dark furnace, Popeye also finds Shorty, and moans that Shorty has ruined everything – and he didn’t even get his birthday cake. Upstairs, the foot of Olive is seen, shoving the unneeded cake down the hole in the floor. It lands inside the furnace pipes, with a plop on Popeye’s head, a single candle still lit to light the scene. Shorty eagerly asks to blow it out, and does, singing “Happy Birthday to my pal” in the total blackness. Suddenly, a pistol shot is heard and its light momentarily seen – aimed in the direction of Shorty, and presumably by the hand of Popeye. From the darkness, letters appear on the screen and slowly approach the camera, underscored by morbid music, reading “The Bitter End.”

Shorty is starting to feel suicidal again, realizing that because of him, Popeye isn’t having any fun – not playing games and stuff as he should on his birthday. Popeye re-enters the apartment, carrying a baseball bat, intending to have some vengeance upon Shorty for his interference. Shorty sees this as an invitation for some indoor baseball, and retrieves a ball. In demonstrating the techniques of Babe Ruth to Popeye in the next room, we hear the clout of wood against ball, and watch Popeye re-enter the room, with the ball repeatedly bouncing off his head. Popeye collapses back into the adjoining room upon a square throw rug, and Shorty darts around its corners, sliding under the rug and upsetting the prone Popeye, as Shorty touhes a furnace grating that serves as home plate. Next. Shorty grabs up a golf club and ball, and demonstrates a Bobby Jones drive, which bounces repeatedly off walls in front of and behinf Popeye, rebounding between wall and Popeye’s head. Popeye falls on his back with mouth open, the ball resting upon his chest, as the pole of a souvenir pennant from Coney Island drops into Popeye’s mouth. Removing the flag, Shorty steps onto Popeye’s chest. “On the green in 1 – now for a birdie”, says Shorty, as he putts the golf ball down Popeye’s throat. Then, indoor ice hockey, with Popeye nearly swallowing the puck. The puck lands between his feet, as Shorty charges. Popeye takes aim with his hockey stick – not at the puck, but at the oncoming Shorty. He takes a wild swing, but misses, causing his skates to spin in a circle, and carve a hole in the wood of the floor. Popeye falls through, but rises again atop the floorboard, which rests as a ceiling atop the head of a gentlemanly British character who lives in the apartment below. The Britisher politely inquires what is going on, then equally-politely apologizes that he must leave, as he is losing his footing. The Britisher falls out of our view, but Popeye leaps off his head just in time, and kicks Shorty down the hole. Enter Olive with the completed birthday cake, as Popeye tries to hide the hole from view with the throw rug. Olive steps directly upon the rug, and falls through, while the cake, slightly wider in diameter than the hole, remains in the room on the floor. Popeye, realizing Olive is in trouble, darts down to the Britisher’s apartment. “She went thata-way”, the Britisher says, pointing to an Olive-shaped hole in his own floor. Popeye runs down four or five more flights to the basement, just as the silhouette of Olive appears with a clang among the basement furnace pipes. Popeye darts into the furnace, but is told by Olive that he and Shorty should never darken her door again. Olive exits, blackened with coal dust. Inside the dark furnace, Popeye also finds Shorty, and moans that Shorty has ruined everything – and he didn’t even get his birthday cake. Upstairs, the foot of Olive is seen, shoving the unneeded cake down the hole in the floor. It lands inside the furnace pipes, with a plop on Popeye’s head, a single candle still lit to light the scene. Shorty eagerly asks to blow it out, and does, singing “Happy Birthday to my pal” in the total blackness. Suddenly, a pistol shot is heard and its light momentarily seen – aimed in the direction of Shorty, and presumably by the hand of Popeye. From the darkness, letters appear on the screen and slowly approach the camera, underscored by morbid music, reading “The Bitter End.”

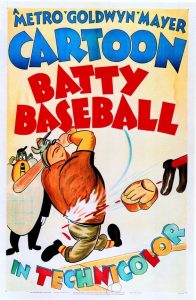

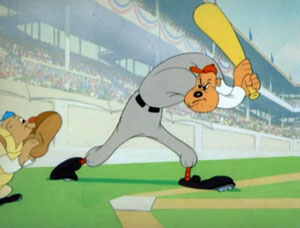

Batty Baseball (MGM, 4/22/44 – Tex Avery, dir.) – Tex takes his one at-bat on the topic subject. Though it contains some creative ideas, and a memorable opening, it somehow falls short, and fails to measure up as one of Avery’s best. In fact, because of the limitations of its plot setup, it always gave me the feeling of being over before it really started. Perhaps this goes properly with its opening, which is started before it’s really begun.

Batty Baseball (MGM, 4/22/44 – Tex Avery, dir.) – Tex takes his one at-bat on the topic subject. Though it contains some creative ideas, and a memorable opening, it somehow falls short, and fails to measure up as one of Avery’s best. In fact, because of the limitations of its plot setup, it always gave me the feeling of being over before it really started. Perhaps this goes properly with its opening, which is started before it’s really begun.

A single card introduces the film, identifying only the title and director. Suddenly, we are in the middle of the action in a straight jump cut. Two teams are at it on the filed, both seeming to have a line-up that consists entirely of players whose last names begin with “Mc”. The mile-a-minute chatter of an announcer attempts to keep up with the action, as a first pitch is clouted, sending an outfielder up the stairs of the field bleachers, backing, backing, until he falls backwards over the unrailed edge of the topmost step. Runners and fielders scramble all over the field like a cycle of running picnic ants. One player is out at the plate, as he gets clobbered over the head by a bat in the catcher’s hands. McDroop heads for home, leaping into the air to begin a slide – then comes to a brake-screeching halt in mid-air. He faces the camera, and addresses the narrator. “Hey, wait a minute. Didn’t ya forget somethin’? Who made this picture? How ‘bout the MGM title, the lion roar, and all that kinda stuff?” The narrator responds, “Oh, I guess I got too excited. I’m sorry, boys.” So, in fades the lion, and the missing animator’s credits! (Would have made for an interesting task had the film ever been chosen for theatrical reissue, as there seems to be no time permitted for slipping Fred Quimby’s name into the credits. However, reissue would have been unlikely, due to the cartoon’s wartime theme.)

Another card fades in, stating “Any similarity between the title of this picture and the story that follows is purely an accident.” Our scene then fades in at a stadium named “W.C. Field”. A superimposed sign appears over the lower portion of the screen, informing us, “The guy who thought of this corny gag isn’t with us any more.” The game commences between the Yankee Doodlers and the Draft Dodgers – though it’s never quite clear which team is which. The pitcher and catcher warm up – in tosses of the ball back and forth from a distance of only two feet apart. The umpire dusts off the plate with a whisk broom – then turns his attentions to the batter’s uniform, also neatly dusting him off, and receiving a tip from the batter for his kind services. One team is down to two players – its pitcher and catcher – due to the draft, all other positions on the field replaced by small signs reading “1A”. The pitcher (McDrip), however, wears on the back of his uniform the number “4F”. This premise limits the film considerably, and, unlike a Bugs Bunny cartoon discussed below which takes even more incredible one-sided odds to an extreme and makes something out of it, this one never seems to get out of the top half of the first inning.

Another card fades in, stating “Any similarity between the title of this picture and the story that follows is purely an accident.” Our scene then fades in at a stadium named “W.C. Field”. A superimposed sign appears over the lower portion of the screen, informing us, “The guy who thought of this corny gag isn’t with us any more.” The game commences between the Yankee Doodlers and the Draft Dodgers – though it’s never quite clear which team is which. The pitcher and catcher warm up – in tosses of the ball back and forth from a distance of only two feet apart. The umpire dusts off the plate with a whisk broom – then turns his attentions to the batter’s uniform, also neatly dusting him off, and receiving a tip from the batter for his kind services. One team is down to two players – its pitcher and catcher – due to the draft, all other positions on the field replaced by small signs reading “1A”. The pitcher (McDrip), however, wears on the back of his uniform the number “4F”. This premise limits the film considerably, and, unlike a Bugs Bunny cartoon discussed below which takes even more incredible one-sided odds to an extreme and makes something out of it, this one never seems to get out of the top half of the first inning.

McDrip goes into a windup, but barely flicks the ball toward home with an effeminate twitch of one wrist. Somehow, a tee mound of raised dirt pops up on the field just ahead of the plate, for the ball to fall neatly upon, and the batter swings his bat underhanded like a golf swing. As the ball heads for the fence, the announcer shouts, “It’s going, going…” On the fence is a large billboard, depicting a lovely starlet with beaming smile, for Toothodent toothpaste with Delirium – the Smile of Glamour. The ball strikes the billboard right upon her smile, knocking loose her front tooth. The announcer completes his sentence, with a slight drop of excitement from his voice: “…Gone.” Angry McDrip sets his sights for the next batter – literally – by producing a flip-out rifle sight from the toe of his shoe, and aiming its cross-hairs directly between the eyes of the waiting batter. A direct-hit bean ball. The batter does not even advance to first. Instead, he gently sets his bat and hat in a pile next to the plate, walks a few slow steps toward first, turns, and keels over backwards into a waiting ambulance stretcher. Two ambulance attendants cart him away into a vehicle marked, “Last aid”, as a few bars of the funeral march play at their departure.

McDrip goes into a windup, but barely flicks the ball toward home with an effeminate twitch of one wrist. Somehow, a tee mound of raised dirt pops up on the field just ahead of the plate, for the ball to fall neatly upon, and the batter swings his bat underhanded like a golf swing. As the ball heads for the fence, the announcer shouts, “It’s going, going…” On the fence is a large billboard, depicting a lovely starlet with beaming smile, for Toothodent toothpaste with Delirium – the Smile of Glamour. The ball strikes the billboard right upon her smile, knocking loose her front tooth. The announcer completes his sentence, with a slight drop of excitement from his voice: “…Gone.” Angry McDrip sets his sights for the next batter – literally – by producing a flip-out rifle sight from the toe of his shoe, and aiming its cross-hairs directly between the eyes of the waiting batter. A direct-hit bean ball. The batter does not even advance to first. Instead, he gently sets his bat and hat in a pile next to the plate, walks a few slow steps toward first, turns, and keels over backwards into a waiting ambulance stretcher. Two ambulance attendants cart him away into a vehicle marked, “Last aid”, as a few bars of the funeral march play at their departure.

McDrip’s famous spit ball doesn’t seem to have much strategic effect offensively. Instead, it merely diverts its course away from the batter, over to a brass spittoon on the sidelines, and spits into it. McDrip’s fast ball is more effective, as he launches three baseballs back-to-back, so fast, the batter fails to react to any of them. When called out, all the burly batter can do is plop down on the dirt stomach-first, and wail like a baby. From the stands, a spectator calls out, “Kill the umpire!” Off-screen, the sound of a shotgun blast is heard – and all of the spectators stand, removing their hats in respect, as a bugler somewhere blows Taps. (We’ll never know if the first ump really died, or had an identical twin, as an umpire looking the same appears in subsequent sequences,)

We are introduced to the cartoon’s running gag – a typically gabby catcher, with an aggravating habit of running out to catch the ball in front of the feet of the batter. McDrip throws his “beautiful curve”, which traces the outline of a shapely dame, prompting a unison wolf whistle from the spectators in the crowd. The pitcher substitutes a bowling ball, and rolls a strike to knock the batter, catcher, and umpire out of the plate area. Then an automatic pin setter lowers as in a bowling alley, to replace the players into their original positions like bowling pins.

We are introduced to the cartoon’s running gag – a typically gabby catcher, with an aggravating habit of running out to catch the ball in front of the feet of the batter. McDrip throws his “beautiful curve”, which traces the outline of a shapely dame, prompting a unison wolf whistle from the spectators in the crowd. The pitcher substitutes a bowling ball, and rolls a strike to knock the batter, catcher, and umpire out of the plate area. Then an automatic pin setter lowers as in a bowling alley, to replace the players into their original positions like bowling pins.

McDrip substitutes an iron ball for the next pitch, stopping the swinging bat in its tracks, and giving the batter a case of reverberating jitters. McDrip approaches to laugh at the situation, but the jitters somehow travel down the batter’s ankles, through the ground, and up the ankles of McDrip, putting him through the same vibrations. Now comes the batting team’s power hitter – a dog of giant proportions, wearing the uniform number “B-19″. McDrip winds up, but emerges from the spin carrying a slingshot, with which he launches the ball. The batter clobbers it, and McDrip is finally forced into a fielding role. He repeats the old ostrich gag from Terry and Van Beuren, swallowing the ball while shouting “I got it.”

The next batter receives repeated pitches that never reach the plate – thanks to a yo-yo string tied around the ball and attached to McDrip’s mitt. The ump calls the batter out, and another irate fan yells that the umpire is blind. Lifting another old gag from “Porky’s Baseball Broadcast”, the umpire turns to face him, wearing dark glasses and holding a white cane and a cup full of pencils to sell, replying, “Oh, I am not.” Finally, the catcher repeats his old tricks at the plate, but this time, a swing by the batter connects – not with the ball, but with the catcher. While the blow is not seen on-screen, the batter reacts with remorse at what he has done, while the narrator announces, “We will now observe one minute of silence.” We actually don’t spend that long, as a small cloud floats upwards past a totally black screen, carrying the angel of the catcher, who holds a sign repeating the ending from Avery’s “The Early Bird Dood it”, reading “Sad ending, isn’t it?”

The next batter receives repeated pitches that never reach the plate – thanks to a yo-yo string tied around the ball and attached to McDrip’s mitt. The ump calls the batter out, and another irate fan yells that the umpire is blind. Lifting another old gag from “Porky’s Baseball Broadcast”, the umpire turns to face him, wearing dark glasses and holding a white cane and a cup full of pencils to sell, replying, “Oh, I am not.” Finally, the catcher repeats his old tricks at the plate, but this time, a swing by the batter connects – not with the ball, but with the catcher. While the blow is not seen on-screen, the batter reacts with remorse at what he has done, while the narrator announces, “We will now observe one minute of silence.” We actually don’t spend that long, as a small cloud floats upwards past a totally black screen, carrying the angel of the catcher, who holds a sign repeating the ending from Avery’s “The Early Bird Dood it”, reading “Sad ending, isn’t it?”

It’s no wonder that this film feels over before it should be, as its running time is a mere 6 minutes and 11 seconds – very short for an Avery film of this vintage. Seems like we could have used about three more gag sequences to fill out the time, but no more were forthcoming from the writers. Hmm…perhaps we should write our own…

• Someone posted BATTY BASEBALL on Facebook HERE!

The Unruly Hare (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 2/10/45 – Frank Tashlin, dir.) – A railroad right-of-way extends directly across the old tree stump which Bugs currently calls home. Surveyor Elmer Fudd enters with tripod and telescope to measure and chart out the route. As expected, Bugs makes his life hell – including by holding a match up in front of his surveying lens, and giving the visual appearance that the woods are on fire. He also makes Elmer’s eyes bug out by holding up before the telescope pin-up images of ersatz “Petty” girls before Elmer’s device, then adding a view of live kissing lips – provided by a little lipstick upon Bugs’s own smoochers. After five minutes of the usual abuse, Elmer can take it no longer, and resorts to the supplies of the railroad company, lighting a stick of dynamite, and dropping it into Bugs’s stump. Elmer flees before the explosion, but Bugs pops up ahead of him, out of a hole serving as a rear entrance to his underground home. As Elmer approaches, Bugs holds out the dynamite stick like the baton in a track-and-field relay race. “C’mon. Elmer. We’ll beat ‘em!”, shouts Bugs, inducing Elmer to increase speed, and snatch the baton to take his part in the speed competition. Elmer progresses forward about twenty or more feet, before realizing what sort of baton he is carrying. He flings the red stick away, right in its path is the waiting Bugs, who is already prepared, with a catcher’s mask, mitt, and a concrete slab already in place for home plate.

The Unruly Hare (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 2/10/45 – Frank Tashlin, dir.) – A railroad right-of-way extends directly across the old tree stump which Bugs currently calls home. Surveyor Elmer Fudd enters with tripod and telescope to measure and chart out the route. As expected, Bugs makes his life hell – including by holding a match up in front of his surveying lens, and giving the visual appearance that the woods are on fire. He also makes Elmer’s eyes bug out by holding up before the telescope pin-up images of ersatz “Petty” girls before Elmer’s device, then adding a view of live kissing lips – provided by a little lipstick upon Bugs’s own smoochers. After five minutes of the usual abuse, Elmer can take it no longer, and resorts to the supplies of the railroad company, lighting a stick of dynamite, and dropping it into Bugs’s stump. Elmer flees before the explosion, but Bugs pops up ahead of him, out of a hole serving as a rear entrance to his underground home. As Elmer approaches, Bugs holds out the dynamite stick like the baton in a track-and-field relay race. “C’mon. Elmer. We’ll beat ‘em!”, shouts Bugs, inducing Elmer to increase speed, and snatch the baton to take his part in the speed competition. Elmer progresses forward about twenty or more feet, before realizing what sort of baton he is carrying. He flings the red stick away, right in its path is the waiting Bugs, who is already prepared, with a catcher’s mask, mitt, and a concrete slab already in place for home plate.

Repeating a bit of the usual talk-it-up banter so common to Warner Brothers’ catchers, Bugs shouts words of encouragement to Elmer, “That’s pitchin’ to ‘em, ol’ kid. Put it right in there, ol’ boy.” Bugs catches the still-lit stick, and tosses it back to Elmer. Gullible Elmer is now as equally convinced he is in a ball game as he was in a relay race, and casually catches the stick, then eases into a wind-up for the next pitch. Suddenly, light dawns in his dome again, and his eyeballs extend about two feet out of his head in shock-take at the fuse burning rapidly down upon the stick in his hand. He once again tosses the stick at Bugs. Bugs realizes there is no time left for a further deception, and leaps out of his baseball gear to beat a fast retreat down the road. Bugs rounds a curve in the path before him, and the dynamite stick somehow diverts course to match his steps – straight toward a large stack of railroad rails and cross-ties. BLAM!!!! A flaming blast envelops the camera shot, and materials fly everywhere. The camera shifts to a long shot of Elmer, watching in disbelief as cross-tie after cross-tie plop down in a neatly-spaced row right up to Elmer’s feet, then behind him and up the railroad bed, followed by rails landing neatly upon each side of the row of ties. The entire railroad is built before us in the twinkling of an eye (never mind the eventual need for spikes to hold it firmly together), and the railroad isn’t wasting time on making use of it. Right behind the track, here comes the first locomotive, and Elmer has to dive off the tracks to get out of the way. As Elmer looks back once the train has passed him, he spots Bugs standing on the rear platform of the caboose, waving goodbye to him. Suddenly, Bugs reacts to a thought which crosses his mind, and unexpectedly jumps from the platform, rolling and landing in the dust upon the track bed below. Why did he jump? This is still wartime, and Bugs just remembered that civilians shouldn’t be doing any unnecessary traveling these days (to keep transportation available for the servicemen). So, Bugs makes the rest of his escape on foot, hiking along the tracks with a bindle stick upon his shoulder, far into the night.

Repeating a bit of the usual talk-it-up banter so common to Warner Brothers’ catchers, Bugs shouts words of encouragement to Elmer, “That’s pitchin’ to ‘em, ol’ kid. Put it right in there, ol’ boy.” Bugs catches the still-lit stick, and tosses it back to Elmer. Gullible Elmer is now as equally convinced he is in a ball game as he was in a relay race, and casually catches the stick, then eases into a wind-up for the next pitch. Suddenly, light dawns in his dome again, and his eyeballs extend about two feet out of his head in shock-take at the fuse burning rapidly down upon the stick in his hand. He once again tosses the stick at Bugs. Bugs realizes there is no time left for a further deception, and leaps out of his baseball gear to beat a fast retreat down the road. Bugs rounds a curve in the path before him, and the dynamite stick somehow diverts course to match his steps – straight toward a large stack of railroad rails and cross-ties. BLAM!!!! A flaming blast envelops the camera shot, and materials fly everywhere. The camera shifts to a long shot of Elmer, watching in disbelief as cross-tie after cross-tie plop down in a neatly-spaced row right up to Elmer’s feet, then behind him and up the railroad bed, followed by rails landing neatly upon each side of the row of ties. The entire railroad is built before us in the twinkling of an eye (never mind the eventual need for spikes to hold it firmly together), and the railroad isn’t wasting time on making use of it. Right behind the track, here comes the first locomotive, and Elmer has to dive off the tracks to get out of the way. As Elmer looks back once the train has passed him, he spots Bugs standing on the rear platform of the caboose, waving goodbye to him. Suddenly, Bugs reacts to a thought which crosses his mind, and unexpectedly jumps from the platform, rolling and landing in the dust upon the track bed below. Why did he jump? This is still wartime, and Bugs just remembered that civilians shouldn’t be doing any unnecessary traveling these days (to keep transportation available for the servicemen). So, Bugs makes the rest of his escape on foot, hiking along the tracks with a bindle stick upon his shoulder, far into the night.

• Watch UNRULY HARE on Vimeo HERE, you Rat!

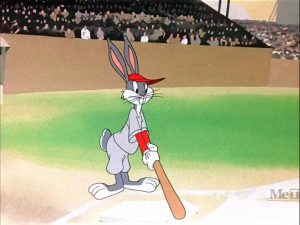

Baseball Bugs (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 2/2/46 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – Story man Michael Maltese teams up with Friz for a memorable at bat that combines some long memories and a few long-ago gags with some new inspiration, that finally provides the studio with a perennial baseball classic, well among the top cartoons ever produced on the sport. At the Polo Grounds, the visiting Gas House Gorillas are giving the home team Tea Totallers a shellacking they’ll never forget. The game is already in progress as we begin, as one of Freleng’s “screaming liners” is hit into left field, straight out of “Porky’s Baseball Broadcast.” A quick change of sides, and the Tea Totallers’ possible star player (only 93 and a half years old) receives a pitch which is called a ball, until the Gorillas’ catcher smashes the umpire into the ground with one clout from his fist. The apologetic and wobbly ump rises partway from the hole in the ground, to utter in a meek voice, “I don’t know what could have come over me, sir. I meant to say, ‘Strike!’” Another quick change of sides, and the entire Gorillas’ roster (a large one at that, of about 40 men – must be late-season expansion time) rounds the bases with non-stop hits in a conga line. The scoreboard is passing 42 runs in this one inning (but someone didn’t do the math, as the combined figures for all innings so far played equals 96 – yet their score is later referred to as 95!). But suddenly, despite the general cheers of the crowd ready to disown the Tea Totallers, a voice of dissent is heard from the middle of the outfield. From a hole in the middle of the field watches Bugs Bunny, equipped with sun hat, peanut bag, pop bottle, and, of course, carrot (a hard thing to find in a baseball concession stand). “Boo! The Gas House Gorillas are a bunch of dirty players. Why I could beat them with one hand tied begind my back, all by myself!” As Bugs pantomimes hitting one home run after another, he is suddenly lifted out of the hole by the ears, and a puff of cigar smoke blown in his face by the Gorillas’ team captain. “All right, big shot. So ya think ya can beat us all by yourself. Well, ya got yourself a game!” The Captain dumps a load of baseball equipment and uniform components upon Bugs, and all Bugs can do is eye the squad of Gorillas around him nervously, realizing he will have to prove his boast. If this sounds anything like the general idea of a certain Willie Whopper cartoon reviewed here a few weeks ago, you’re right. Only Bugs, despite the borrowing of his writers, manages to make the concept his own, as we will see.

Baseball Bugs (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 2/2/46 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – Story man Michael Maltese teams up with Friz for a memorable at bat that combines some long memories and a few long-ago gags with some new inspiration, that finally provides the studio with a perennial baseball classic, well among the top cartoons ever produced on the sport. At the Polo Grounds, the visiting Gas House Gorillas are giving the home team Tea Totallers a shellacking they’ll never forget. The game is already in progress as we begin, as one of Freleng’s “screaming liners” is hit into left field, straight out of “Porky’s Baseball Broadcast.” A quick change of sides, and the Tea Totallers’ possible star player (only 93 and a half years old) receives a pitch which is called a ball, until the Gorillas’ catcher smashes the umpire into the ground with one clout from his fist. The apologetic and wobbly ump rises partway from the hole in the ground, to utter in a meek voice, “I don’t know what could have come over me, sir. I meant to say, ‘Strike!’” Another quick change of sides, and the entire Gorillas’ roster (a large one at that, of about 40 men – must be late-season expansion time) rounds the bases with non-stop hits in a conga line. The scoreboard is passing 42 runs in this one inning (but someone didn’t do the math, as the combined figures for all innings so far played equals 96 – yet their score is later referred to as 95!). But suddenly, despite the general cheers of the crowd ready to disown the Tea Totallers, a voice of dissent is heard from the middle of the outfield. From a hole in the middle of the field watches Bugs Bunny, equipped with sun hat, peanut bag, pop bottle, and, of course, carrot (a hard thing to find in a baseball concession stand). “Boo! The Gas House Gorillas are a bunch of dirty players. Why I could beat them with one hand tied begind my back, all by myself!” As Bugs pantomimes hitting one home run after another, he is suddenly lifted out of the hole by the ears, and a puff of cigar smoke blown in his face by the Gorillas’ team captain. “All right, big shot. So ya think ya can beat us all by yourself. Well, ya got yourself a game!” The Captain dumps a load of baseball equipment and uniform components upon Bugs, and all Bugs can do is eye the squad of Gorillas around him nervously, realizing he will have to prove his boast. If this sounds anything like the general idea of a certain Willie Whopper cartoon reviewed here a few weeks ago, you’re right. Only Bugs, despite the borrowing of his writers, manages to make the concept his own, as we will see.

The stadium announcer describes a “slight change” in the Tea Totaller lineup, rattling through all nine positions, all now being covered by Bugs Bunny. This obviously puts Bugs in a position Willie Whopper never faced. Since he will be the only batter, in order to play under regulation rules, this would require Bugs to hit a home run every time, as any attempt to return to the plate for his next at bat upon a mere base hit would take him off the bag, allowing him to be tagged immediately out. Is Bugs up to the challenge? As Red Skelton might have said, “We know him very well, don’t we?” Bugs begins his duties on the pitcher’s mound. In order to accomplish this task single-handed, he has to adopt Max Hare’s speed, outracing the ball each time he pitches it, arriving at the plate in time to don catcher’s gear, and even provide the usual Freleng catcher’s chatter to himself while in the catcher’s role, before, as usual, getting knocked to the backstop by the force of each pitch. Bugs then delivers the old slow ball, and is so confident about it, he doesn’t even run to the plate to act as catcher. The ball merely floats by three consecutive batters, all on the same pitch. Each takes three wild swings at the same ball, all of which are tallied as strikes by the umpire, striking out the entire side on one throw.

The stadium announcer describes a “slight change” in the Tea Totaller lineup, rattling through all nine positions, all now being covered by Bugs Bunny. This obviously puts Bugs in a position Willie Whopper never faced. Since he will be the only batter, in order to play under regulation rules, this would require Bugs to hit a home run every time, as any attempt to return to the plate for his next at bat upon a mere base hit would take him off the bag, allowing him to be tagged immediately out. Is Bugs up to the challenge? As Red Skelton might have said, “We know him very well, don’t we?” Bugs begins his duties on the pitcher’s mound. In order to accomplish this task single-handed, he has to adopt Max Hare’s speed, outracing the ball each time he pitches it, arriving at the plate in time to don catcher’s gear, and even provide the usual Freleng catcher’s chatter to himself while in the catcher’s role, before, as usual, getting knocked to the backstop by the force of each pitch. Bugs then delivers the old slow ball, and is so confident about it, he doesn’t even run to the plate to act as catcher. The ball merely floats by three consecutive batters, all on the same pitch. Each takes three wild swings at the same ball, all of which are tallied as strikes by the umpire, striking out the entire side on one throw.

Bugs now steps up to the plate. He calls for the “bat boy” and receives a bat from Freleng’s winged mutant, somewhat redesigned from “Porky’s Baseball Broadcast”. Bugs has enough dexterity that he is able to flip his bat into the air, long enough to rub his hands together to dry them off, then catch the descending bat in time to swing a hit upon the first pitch. Bugs rounds the bases, but finds the Gorilla catcher calmly waiting with the ball at the plate. So Bugs diverts his attention – flashing before his eyes a girlie pin-up poster. The catcher’s eyes bug out, and he begins hopping around ga-ga, with shouts of “Wow” and Woo-woo”, bouncing off the plate and on down the baseline, as Bugs crosses the plate unopposed for his first run. For his next at bat, Bugs again gets a hit and rounds the bases, but dirty work is afoot. The umpire is waylaid by one of the Gorillas, who changes gear with him behind the fence, and makes an appearance posing as the ump. “Yer out!”, he shouts as Bugs crosses the plate. Bugs appears, inside the Gorilla’s catcher’s mask, protesting the call face to face. “Where do ya get that malarkey? I’m safe”, shouts Bugs. The Gorilla repeats the call, and an alternating banter of “Out” and “Safe” issues between the two. Then Maltese pulls a twist on words that would become a favorite staple in later years between Bugs and Daffy, as Bugs does a switcheroo, yelling “Out”, prompting the Gorilla to reflexively yell the opposite: “Safe!” Finally, the Gorilla puts his foot down. “I say you’re safe! It you don’t like it, you can go to the showers.” Bugs graciously concedes the argument. “Have it your way. I’m safe.” Bugs disappears, and only a few moments later does the Gorilla realize what he has called, as the scoreboard totes up another run for Bugs.

Bugs now steps up to the plate. He calls for the “bat boy” and receives a bat from Freleng’s winged mutant, somewhat redesigned from “Porky’s Baseball Broadcast”. Bugs has enough dexterity that he is able to flip his bat into the air, long enough to rub his hands together to dry them off, then catch the descending bat in time to swing a hit upon the first pitch. Bugs rounds the bases, but finds the Gorilla catcher calmly waiting with the ball at the plate. So Bugs diverts his attention – flashing before his eyes a girlie pin-up poster. The catcher’s eyes bug out, and he begins hopping around ga-ga, with shouts of “Wow” and Woo-woo”, bouncing off the plate and on down the baseline, as Bugs crosses the plate unopposed for his first run. For his next at bat, Bugs again gets a hit and rounds the bases, but dirty work is afoot. The umpire is waylaid by one of the Gorillas, who changes gear with him behind the fence, and makes an appearance posing as the ump. “Yer out!”, he shouts as Bugs crosses the plate. Bugs appears, inside the Gorilla’s catcher’s mask, protesting the call face to face. “Where do ya get that malarkey? I’m safe”, shouts Bugs. The Gorilla repeats the call, and an alternating banter of “Out” and “Safe” issues between the two. Then Maltese pulls a twist on words that would become a favorite staple in later years between Bugs and Daffy, as Bugs does a switcheroo, yelling “Out”, prompting the Gorilla to reflexively yell the opposite: “Safe!” Finally, the Gorilla puts his foot down. “I say you’re safe! It you don’t like it, you can go to the showers.” Bugs graciously concedes the argument. “Have it your way. I’m safe.” Bugs disappears, and only a few moments later does the Gorilla realize what he has called, as the scoreboard totes up another run for Bugs.

A quick and classic gag follows Bugs’s next hit. A Gorilla fielder charges the ball, yelling “I got it. I got it.” The ball slams into his chest, driving him headfirst into the ground, where the earth rises in the form of a grave, complete with gravestone reading “He got it.” Another hit smacks a cigar-chomping Gorilla right in the “butt” (the one between his lips, that is), knocking him back to the outfield fence with his cigar well-smashed, against a billboard bearing the slogan, “Does your tobacco taste different lately?” (Slogan for Walter Raleigh pipe tobacco.) Another hit somewhat mirrors Bluto’s pinball-machine sock from The Twisker Pitcher, bouncing off the heads of every player on the field – but adds a new twist, as the scoreboard lights up in neon-colored random numbers in each score box, them adds a lighted readout stating “Tilted”. A quick change of sides, and a Gorilla takes an at bat. He seems to score a hit, and rounds the bases, but Bugs waits at the plate, and punches him in the midriff with the ball concealed within Bugs’s fist. The Gorilla sits on the baseline in a stupor, as visions of little baseball players circle his head, tossing baseballs to each other. Bugs hold up a sign to the audience, with the old wartime slogan, “Was this trop really necessary?” A radio-style scorebiard jungle is heard over the loudspeaker system, announcing the current score as we go into the ninth inning. “Bugs Bunny, 96, Gas House Gorillas, 95.”

A quick and classic gag follows Bugs’s next hit. A Gorilla fielder charges the ball, yelling “I got it. I got it.” The ball slams into his chest, driving him headfirst into the ground, where the earth rises in the form of a grave, complete with gravestone reading “He got it.” Another hit smacks a cigar-chomping Gorilla right in the “butt” (the one between his lips, that is), knocking him back to the outfield fence with his cigar well-smashed, against a billboard bearing the slogan, “Does your tobacco taste different lately?” (Slogan for Walter Raleigh pipe tobacco.) Another hit somewhat mirrors Bluto’s pinball-machine sock from The Twisker Pitcher, bouncing off the heads of every player on the field – but adds a new twist, as the scoreboard lights up in neon-colored random numbers in each score box, them adds a lighted readout stating “Tilted”. A quick change of sides, and a Gorilla takes an at bat. He seems to score a hit, and rounds the bases, but Bugs waits at the plate, and punches him in the midriff with the ball concealed within Bugs’s fist. The Gorilla sits on the baseline in a stupor, as visions of little baseball players circle his head, tossing baseballs to each other. Bugs hold up a sign to the audience, with the old wartime slogan, “Was this trop really necessary?” A radio-style scorebiard jungle is heard over the loudspeaker system, announcing the current score as we go into the ninth inning. “Bugs Bunny, 96, Gas House Gorillas, 95.”

Another foul-up by the writers. The Gas House Gorillas were the visiting team, so should bat first in the ninth inning. Instead, the announcer states they are up in the bottom of the ninth! Two out, and a man on base. “A home run now would win the game for the Gorillas.” The Gorilla captain waits in the batter’s box, but upon hearing what the announcer says, decides a more appropriate weapon is required. He steps outside the stadium, and chops down the biggest tree he can spot. Thus, he steps up to the plate with a mammoth wooden log with one end carved into a handle. Confident Bugs asides to the audience: “Eh, watch me paste this pathetic palooka with a powerful paralyzing perfect pachydermus percussion pitch.” (Does “pachydermus” suggest that this pitch would stun an elephant?) After a windup that has so many shifts of gears, a competent ump might call it a balk, Bugs lets the ball fly – and fly it does, straight out of the park at the force of the batter’s blow. Again, memories of Willie Whopper are present, as Bugs engages in a similar pursuit of the ball across the city of New York. First, he hails a taxi, and directs it to “Follow that ball.” Once inside it, Bugs is surprised when the driver deliberately speeds in the wrong direction. Not a surprise, when Bugs sees a pictorial placard inside the cab, reading “Your Driver” – the Gorilla captain. (Interesting that he handles the matter himself, instead of being concerned about rounding the bases inside the park.) Bugs ditches the cab at a bus stop, and hops aboard a bus going the other way. Bugs casually reads a newspaper on board, as he glances out the window to keep track of the still soaring baseball above. (These New York buses must be plenty fast to keep up with it.) Bugs gets off at the Umpire State Building, and takes the elevator to the roof. There, he hooks his uniform collar onto the rope of the roof flagpole, then hoists himself to the top. With precision timing, Bugs tosses his catching glove high into the air, about twenty feet straight up, where it intersects the path of the ball, catches it, then gently plops down upon Bugs’ wrist. At this moment, the Gorillas’ captain catches up with Bugs from the elevator, arriving at the base of the flagpole. In an even more extraordinary feat than Bugs’s catch, the umpire, who must have a second career as a human fly, appears from over the building railing, to call the batter out. “I’m out?”, grumbles the Gorilla. In a final remembrance of Willie Whopper, the Statue of Liberty in the bay gets into the act, coming to life, and jabbering, “That’s what the man said. You heard what he said. He said that.” (A catch-phrase attributable to Eddie “Rochester” Anderson.) Bugs joins in the non-stop banter with the same words from the flagpole, as the cartoon irises out. The film end with the seldom-seen Looney Tunes ending first seen in “Hare Tonic”, of Bugs bursting out of the Looney Tunes drum, stating, “And that’s the end” while chomping his carrot.

Another foul-up by the writers. The Gas House Gorillas were the visiting team, so should bat first in the ninth inning. Instead, the announcer states they are up in the bottom of the ninth! Two out, and a man on base. “A home run now would win the game for the Gorillas.” The Gorilla captain waits in the batter’s box, but upon hearing what the announcer says, decides a more appropriate weapon is required. He steps outside the stadium, and chops down the biggest tree he can spot. Thus, he steps up to the plate with a mammoth wooden log with one end carved into a handle. Confident Bugs asides to the audience: “Eh, watch me paste this pathetic palooka with a powerful paralyzing perfect pachydermus percussion pitch.” (Does “pachydermus” suggest that this pitch would stun an elephant?) After a windup that has so many shifts of gears, a competent ump might call it a balk, Bugs lets the ball fly – and fly it does, straight out of the park at the force of the batter’s blow. Again, memories of Willie Whopper are present, as Bugs engages in a similar pursuit of the ball across the city of New York. First, he hails a taxi, and directs it to “Follow that ball.” Once inside it, Bugs is surprised when the driver deliberately speeds in the wrong direction. Not a surprise, when Bugs sees a pictorial placard inside the cab, reading “Your Driver” – the Gorilla captain. (Interesting that he handles the matter himself, instead of being concerned about rounding the bases inside the park.) Bugs ditches the cab at a bus stop, and hops aboard a bus going the other way. Bugs casually reads a newspaper on board, as he glances out the window to keep track of the still soaring baseball above. (These New York buses must be plenty fast to keep up with it.) Bugs gets off at the Umpire State Building, and takes the elevator to the roof. There, he hooks his uniform collar onto the rope of the roof flagpole, then hoists himself to the top. With precision timing, Bugs tosses his catching glove high into the air, about twenty feet straight up, where it intersects the path of the ball, catches it, then gently plops down upon Bugs’ wrist. At this moment, the Gorillas’ captain catches up with Bugs from the elevator, arriving at the base of the flagpole. In an even more extraordinary feat than Bugs’s catch, the umpire, who must have a second career as a human fly, appears from over the building railing, to call the batter out. “I’m out?”, grumbles the Gorilla. In a final remembrance of Willie Whopper, the Statue of Liberty in the bay gets into the act, coming to life, and jabbering, “That’s what the man said. You heard what he said. He said that.” (A catch-phrase attributable to Eddie “Rochester” Anderson.) Bugs joins in the non-stop banter with the same words from the flagpole, as the cartoon irises out. The film end with the seldom-seen Looney Tunes ending first seen in “Hare Tonic”, of Bugs bursting out of the Looney Tunes drum, stating, “And that’s the end” while chomping his carrot.

This film has gone through substantial restoration work, after a period where the master negatives seemed to fade to a degree where the grass green had nearly disintegrated to gray. While the current prints are massively improved, I remember seeing what must have been an IB Technicolor 16mm print on a large screen in a full-school assembly at a grammar school in Malden, Massachusetts in my childhood, in days when the title was not commonly shown in my local TV market, and when most TV’s people could afford were only in black and white. The screening made a lasting impression upon me, and scored big-time with the junior audience, and I can still see in my mind’s eye several shots of the film on that screen, including the Statue of Liberty ending. I SWEAR the colors were more vibrant on that print than on any I have seen since. One wonders if it or any prints like it still exist in private hands.

This film has gone through substantial restoration work, after a period where the master negatives seemed to fade to a degree where the grass green had nearly disintegrated to gray. While the current prints are massively improved, I remember seeing what must have been an IB Technicolor 16mm print on a large screen in a full-school assembly at a grammar school in Malden, Massachusetts in my childhood, in days when the title was not commonly shown in my local TV market, and when most TV’s people could afford were only in black and white. The screening made a lasting impression upon me, and scored big-time with the junior audience, and I can still see in my mind’s eye several shots of the film on that screen, including the Statue of Liberty ending. I SWEAR the colors were more vibrant on that print than on any I have seen since. One wonders if it or any prints like it still exist in private hands.

• Watch BASEBALL BUGS on Vimeo.

Bored of Education (Paramount/Famous, Little Lulu, 3/1/46 – Bill Tytla, dir.) – An imaginative romp through school and history lessons begins with the usual “Good Morning to You” song at school, Lulu blowing her nose at the end of the tune like a raspberry. Her next-desk neighbor is Tubby, with whom she maintains an ongoing rivalry. Tubby decides to make points with the teacher by snitching an apple from Lulu’s lunch, and presenting it to teacher to get in his good graces. Discovering the theft, Lulu makes a quick switch of objects on the teacher’s desk, substituting in place of the apple her pet frog. The professor is not impressed, and Tubby receives some offscreen whacks with a ruler, while Lulu shows off to Tubby the core of the apple which she has eaten herself.

Next comes history. Lulu is called by the teacher, but has no idea of the answers. Looking around nervously, she spots Tubby holding out a slate in her direction with a date on it, and assumes he is trying to help her. Instead, all his answers are deliberately wrong, so Lulu identifies 1492 as the year the pilgrims landed, and 1776 as the year Columbus discovered America. The teacher tries one more question: “When did Ben Franklin die?” “Did he die? I didn’t even know he was sick”, responds Lulu. That’s all the teacher can stand, and Lulu is sent to the dunce’s stool to study her lesson, while Tubby grins ear to ear in sweet revenge. Lulu tries to concentrate on the book, but falls asleep. In her dream, the book grows to giant proportions, big enough to leap into its illustrations. From the stern of Columbus’s ship, Lulu hears the taunting voice of Tubby, “Hey, Lulu, when did Columbus discover America?” Lulu jumps into the picture to seek out Tubby, but finds a fat captain in pantaloons, talking in a fake Italian accent and claiming to be Columbus. Of course, it is Tubby in disguise, and the two witness the discovery of America, as Tubby sights in his spyglass a shore covered in Indian-style advertisements, including for “White Howl” cigars (play on “White Owl”), “Bow and Arrow Collars” (reference to the “Arrow” shirt company), and “Four Noses Fire Water” (play on “Four Roses” bourbon). Lulu “plants” the flag, which grows out of the ground from a seed by adding water, then she and Tubby shoot off Roman candles to celebrate the event – until Lulu recognizes Tubby at last, and turns the spray of fireworks upon him. Tubby races for the pages of the book, running atop them, and disappears into the next chapter, with Lulu close behind.

Next comes history. Lulu is called by the teacher, but has no idea of the answers. Looking around nervously, she spots Tubby holding out a slate in her direction with a date on it, and assumes he is trying to help her. Instead, all his answers are deliberately wrong, so Lulu identifies 1492 as the year the pilgrims landed, and 1776 as the year Columbus discovered America. The teacher tries one more question: “When did Ben Franklin die?” “Did he die? I didn’t even know he was sick”, responds Lulu. That’s all the teacher can stand, and Lulu is sent to the dunce’s stool to study her lesson, while Tubby grins ear to ear in sweet revenge. Lulu tries to concentrate on the book, but falls asleep. In her dream, the book grows to giant proportions, big enough to leap into its illustrations. From the stern of Columbus’s ship, Lulu hears the taunting voice of Tubby, “Hey, Lulu, when did Columbus discover America?” Lulu jumps into the picture to seek out Tubby, but finds a fat captain in pantaloons, talking in a fake Italian accent and claiming to be Columbus. Of course, it is Tubby in disguise, and the two witness the discovery of America, as Tubby sights in his spyglass a shore covered in Indian-style advertisements, including for “White Howl” cigars (play on “White Owl”), “Bow and Arrow Collars” (reference to the “Arrow” shirt company), and “Four Noses Fire Water” (play on “Four Roses” bourbon). Lulu “plants” the flag, which grows out of the ground from a seed by adding water, then she and Tubby shoot off Roman candles to celebrate the event – until Lulu recognizes Tubby at last, and turns the spray of fireworks upon him. Tubby races for the pages of the book, running atop them, and disappears into the next chapter, with Lulu close behind.

Further adventures in history follow, visiting a Pilgrim village in a parody of “The Courtship of Miles Standish”, Lexington for the ride of Paul (Tubby) Revere, and Bunker Hill (where Lulu forces red-coated and sunglassed Tubby to show the whites of his eyes by the irresistible sight of her slurping on the world’s largest ice cream cone, causing Tubby’s eyes to burst right through the darkened lenses of his glasses). Suddenly, the Wild West, as Lulu pursues him past a settlers’ camp, where an old scout warns that Injuns are coming after their scalps. He activates a siren, with a sign reading “Hair Raid Alarm”. “But where are the Indians?”, asks Lulu. From behind a rock, an Indian appears, dressed in a baseball uniform, and states, “We’re in the American League”.

Further adventures in history follow, visiting a Pilgrim village in a parody of “The Courtship of Miles Standish”, Lexington for the ride of Paul (Tubby) Revere, and Bunker Hill (where Lulu forces red-coated and sunglassed Tubby to show the whites of his eyes by the irresistible sight of her slurping on the world’s largest ice cream cone, causing Tubby’s eyes to burst right through the darkened lenses of his glasses). Suddenly, the Wild West, as Lulu pursues him past a settlers’ camp, where an old scout warns that Injuns are coming after their scalps. He activates a siren, with a sign reading “Hair Raid Alarm”. “But where are the Indians?”, asks Lulu. From behind a rock, an Indian appears, dressed in a baseball uniform, and states, “We’re in the American League”.

A tribe pursues Lulu, who leads them to Ponce De Leon’s fountain of youth, tripping them into the water with a rope across their path. Each of the warriors emerge from the water as babies, while Lulu sings, “One little, two little, three little Indians…” The last “Indian”, however, is Tubby, as the Tenth little Indian boy, who douses Lulu with a bucket of water from the fountain. Lulu shrinks out of her dress, reverting back to an infant, and sits on the ground crying. The scene transforms back to the present, where Lulu is still in a semi-doze from her dream, awakening to find that the fountain water is actually a shot from a water pistol held by Tubby at his desk. Tubby decides to take the idea one better, reloading his water pistol with ink from his inkwell. Lulu spots the tactic, and defends herself by holding up her history book as a shield, causing the ink to rebound off the book, straight into the teacher’s face. With the telltale drippings of ink pointing straight to Tubby, the blue-faced teacher rises from his desk, ruler at the ready, ordering Tubby, “Hold out your hand.” Obviously, however, Tubby’s hand wasn’t the intended target, as the final shot shows Tubby walking back home, with a glowing red sore butt, Lulu walking behind to fan it, laughing, “Boy, you sure stuck your neck out that time!”.

A tribe pursues Lulu, who leads them to Ponce De Leon’s fountain of youth, tripping them into the water with a rope across their path. Each of the warriors emerge from the water as babies, while Lulu sings, “One little, two little, three little Indians…” The last “Indian”, however, is Tubby, as the Tenth little Indian boy, who douses Lulu with a bucket of water from the fountain. Lulu shrinks out of her dress, reverting back to an infant, and sits on the ground crying. The scene transforms back to the present, where Lulu is still in a semi-doze from her dream, awakening to find that the fountain water is actually a shot from a water pistol held by Tubby at his desk. Tubby decides to take the idea one better, reloading his water pistol with ink from his inkwell. Lulu spots the tactic, and defends herself by holding up her history book as a shield, causing the ink to rebound off the book, straight into the teacher’s face. With the telltale drippings of ink pointing straight to Tubby, the blue-faced teacher rises from his desk, ruler at the ready, ordering Tubby, “Hold out your hand.” Obviously, however, Tubby’s hand wasn’t the intended target, as the final shot shows Tubby walking back home, with a glowing red sore butt, Lulu walking behind to fan it, laughing, “Boy, you sure stuck your neck out that time!”.

Jack Kinney returns to the world of baseball, for Casey at the Bat, a segment from the Disney package feature, Make Mine Music (Disney/RKO, 4/20/46). The classic poem receives possibly its umpteenth filming, but this time in animated form. Mudville plays its most famous game, the score 4 to 2 against them, in the final inning. Cooney is first to bat – offering nothing but 300 pounds of fat. He bunts, and narrator Jerry Colonna points out that Cooney maintains his batting average – dying at first base, as usual. The next batter socks a beauty – right in the pitcher’s mitt. Two out. The home fans would lay even money were Casey at the bat. But instead, they get Flynn, a slim guy with a long handlebar moustache, who keeps getting his facial hair entwined around the bat – which is responsible for him pulling in the bat at the right time, hitting a single, much to his own surprise. Though his moustache remains fastened to the bat during his entire run down the baseline, tripping up his progress, he touches first base with the other tip of his moustache, and is called safe. No-hit Jimmy Bake is next, and is the victim of a prank by the opposing catcher, who gives him a hotfoot. The gag backfires, as Blake waves the bat around wildly, clouting a double, and runs twice as fast as usual due to his flaming foot. Men on second and third.

Jack Kinney returns to the world of baseball, for Casey at the Bat, a segment from the Disney package feature, Make Mine Music (Disney/RKO, 4/20/46). The classic poem receives possibly its umpteenth filming, but this time in animated form. Mudville plays its most famous game, the score 4 to 2 against them, in the final inning. Cooney is first to bat – offering nothing but 300 pounds of fat. He bunts, and narrator Jerry Colonna points out that Cooney maintains his batting average – dying at first base, as usual. The next batter socks a beauty – right in the pitcher’s mitt. Two out. The home fans would lay even money were Casey at the bat. But instead, they get Flynn, a slim guy with a long handlebar moustache, who keeps getting his facial hair entwined around the bat – which is responsible for him pulling in the bat at the right time, hitting a single, much to his own surprise. Though his moustache remains fastened to the bat during his entire run down the baseline, tripping up his progress, he touches first base with the other tip of his moustache, and is called safe. No-hit Jimmy Bake is next, and is the victim of a prank by the opposing catcher, who gives him a hotfoot. The gag backfires, as Blake waves the bat around wildly, clouting a double, and runs twice as fast as usual due to his flaming foot. Men on second and third.

Enter Casey, as a solid row of female fans in the front row swoon. A song tells us that the girls don’t know a strike from a foul or a hit, but when Casey plays, the game’s got “it”. Casey is batting 1,000 percent – with the ladies. Colonna croons, “He was the Sinatra of 1902.” The pitcher’s knees knock nervously, while Flynn taunts him with a long lead off third, and Blake makes faces at him with gestures that the pitcher will choke. The catcher wiggles his fingers under his glove in attempt to impart a signal to the pitcher – but his fingers entwine in a braid, complete with a ribbon bowknot. The pitcher stretches his tight collar, a gush of steam emitting from within. A sneer curls Casey’s lips – which can only be described by watching, not reading. The first pitch sails to Casey. Casey fails to lift the bat. The ball merely stops when alongside him, allowing Casey to pluck it from the air, examine it, then toss it away, remarking “That ain’t my style.” Strike 1. A tumult rises from the stands, and a cutie in the first row calls, “Kill the Umpire”, reaching for her hatpin as a weapon. But, in an act of Christian charity, Casey stills the multitude with an upraised hand, and bids the game to go on. Once more the spheroid flew – but Casey still ignores it (sitting on the handle of his bat while reading the Police Gazette), and the umpire calls “Strike 2.” Now Casey’s teeth clench in hate, he pounds his bat upon the plate, and the crowd knows he will not let the ball go by again. The air is shattered by the force of Casey’s blow, which whisks us to a peaceful panorama in a city park, where the words of the poet observe that somewhere hearts are laughing, somewhere children shout. But we return to Mudville, where there is no joy – Mighty Casey has struck out. The weeping Casey stands at night in an empty ballpark in a thundering rainstorm, and his tears turn to anger, as he attempts to pound with his bat at the ball, lying in a puddle at his feet. The ball takes on a life of its own, dodging every attempt by Casey to hit it, and Casey ends the short pursuing the bouncing ball willy-nilly all over the field, as all but the raindrops fade out, and Colonna at last ceases his prolonged final musical note, to observe, “Well, what do you know? The game is over.”

Enter Casey, as a solid row of female fans in the front row swoon. A song tells us that the girls don’t know a strike from a foul or a hit, but when Casey plays, the game’s got “it”. Casey is batting 1,000 percent – with the ladies. Colonna croons, “He was the Sinatra of 1902.” The pitcher’s knees knock nervously, while Flynn taunts him with a long lead off third, and Blake makes faces at him with gestures that the pitcher will choke. The catcher wiggles his fingers under his glove in attempt to impart a signal to the pitcher – but his fingers entwine in a braid, complete with a ribbon bowknot. The pitcher stretches his tight collar, a gush of steam emitting from within. A sneer curls Casey’s lips – which can only be described by watching, not reading. The first pitch sails to Casey. Casey fails to lift the bat. The ball merely stops when alongside him, allowing Casey to pluck it from the air, examine it, then toss it away, remarking “That ain’t my style.” Strike 1. A tumult rises from the stands, and a cutie in the first row calls, “Kill the Umpire”, reaching for her hatpin as a weapon. But, in an act of Christian charity, Casey stills the multitude with an upraised hand, and bids the game to go on. Once more the spheroid flew – but Casey still ignores it (sitting on the handle of his bat while reading the Police Gazette), and the umpire calls “Strike 2.” Now Casey’s teeth clench in hate, he pounds his bat upon the plate, and the crowd knows he will not let the ball go by again. The air is shattered by the force of Casey’s blow, which whisks us to a peaceful panorama in a city park, where the words of the poet observe that somewhere hearts are laughing, somewhere children shout. But we return to Mudville, where there is no joy – Mighty Casey has struck out. The weeping Casey stands at night in an empty ballpark in a thundering rainstorm, and his tears turn to anger, as he attempts to pound with his bat at the ball, lying in a puddle at his feet. The ball takes on a life of its own, dodging every attempt by Casey to hit it, and Casey ends the short pursuing the bouncing ball willy-nilly all over the field, as all but the raindrops fade out, and Colonna at last ceases his prolonged final musical note, to observe, “Well, what do you know? The game is over.”

Lastly, The Great Piggy Bank Robbery (Warner, Daffy Duck, 7/20/46 – Robert Clampett, dir.) receives honorable mention. Clampett’s brilliant, well-remembered send-up of the Dick Tracy comic strip (possibly with Chester Gould’s nodding approval, considering the character receives a free plug by actual name in the film) includes a classic dream-sequence confrontation between Duck Twacy (Daffy) and an entire rogue’s gallery of villains resembling the eccentric names and designs which Gould regularly attributed to his own large cast of villains and hoodlums (such as Flat Top, Prune Face, Mumbles, etc.) Among the new Clampett villains too numerous to recount here are both “Batman” (an anthropomorphic living baseball bat with arms, legs, and facial features etched upon its wood), and “Double-Header” (a uniformed baseball player with two faces conjoined at the rear like a Siamese twin). Their particular powers or crime specialties are never revealed, as they are quickly lost in a group fight cloud, then gunned down with the rest of the gang by Daffy’s merciless machine-gun fire.

Lastly, The Great Piggy Bank Robbery (Warner, Daffy Duck, 7/20/46 – Robert Clampett, dir.) receives honorable mention. Clampett’s brilliant, well-remembered send-up of the Dick Tracy comic strip (possibly with Chester Gould’s nodding approval, considering the character receives a free plug by actual name in the film) includes a classic dream-sequence confrontation between Duck Twacy (Daffy) and an entire rogue’s gallery of villains resembling the eccentric names and designs which Gould regularly attributed to his own large cast of villains and hoodlums (such as Flat Top, Prune Face, Mumbles, etc.) Among the new Clampett villains too numerous to recount here are both “Batman” (an anthropomorphic living baseball bat with arms, legs, and facial features etched upon its wood), and “Double-Header” (a uniformed baseball player with two faces conjoined at the rear like a Siamese twin). Their particular powers or crime specialties are never revealed, as they are quickly lost in a group fight cloud, then gunned down with the rest of the gang by Daffy’s merciless machine-gun fire.

NEXT WEEK: Little Lulu, Gandy Goose, and a host of one-shots provide some middle-inning action – and a new take upon baseball in a foreign land.