Animator Breakdown: “The Greatest Man in Siam” (1944)

August 1944 trade advertisement which advertises “Miss XTC” – promoting a Swing Symphony based on “Lili Marlene” (which was never produced).

The musical framework of Shamus Culhane’s The Greatest Man in Siam, his fourth cartoon as a director for Walter Lantz, came from the novelty tune “Siam.” Spike Jones and His City Slickers recorded “Siam” in April 1942, for a July release on the Bluebird label. Del Porter, a key member of Spike’s band (lead vocalist, clarinetist, and arranger), co-wrote the song with Carl Hoefle. In May 1943, the two composers sold their song to Lantz as an option for one of his Swing Symphonies. For all male voices in Siam, Culhane hired Harry E. Lang (1894-1953), a reliable character actor in film and radio who is heard in several cartoons. Another Porter-Hoefle tune, Pass the Biscuits Mirandy, spawned its own Swing Symphony—Shamus’ first production for Lantz—released in August 1943.

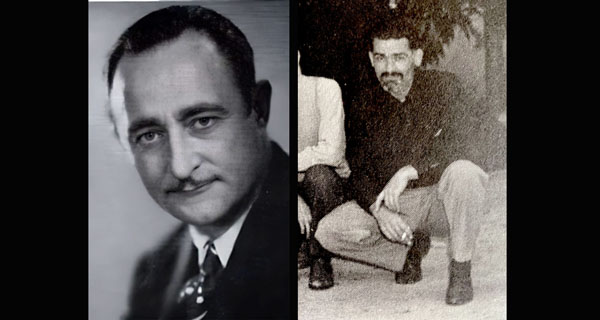

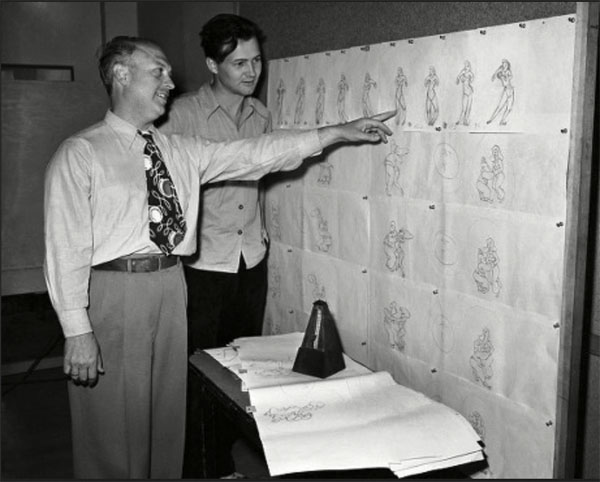

Harry E.Lang (left), Art Heinemann (right)

Art Heinemann, Siam’s layout artist and character designer, moved to Lantz after a brief term at Leon Schlesinger’s, which Culhane had also worked. Shamus and Art’s few months together in the Chuck Jones unit profoundly impacted the two artists. Their interpretation of Chuck’s character design principles and visual flourishes helped develop them as a major creative force at Lantz’s studio. Their work occasioned a seismic shift in Lantz’s modus operandi.

Siam’s ingenious background and color styling gave the film (and subsequent Lantz cartoons) an innovative appearance. Instead of watercolors, Art Heinemann and scenic artist Phil De Guard incorporated paper cut-outs. Designs were sketched, then traced on varicolored paper, cut out, and pasted onto the background mat. For a final touch, the Middle Eastern architectural features were outlined with crayon. This collage technique was a brilliant effect that reduced labor costs for the budget-conscious Lantz. (A year after Siam’s release, Phil De Guard moved to Warners, where he became Chuck Jones’s key background painter.)

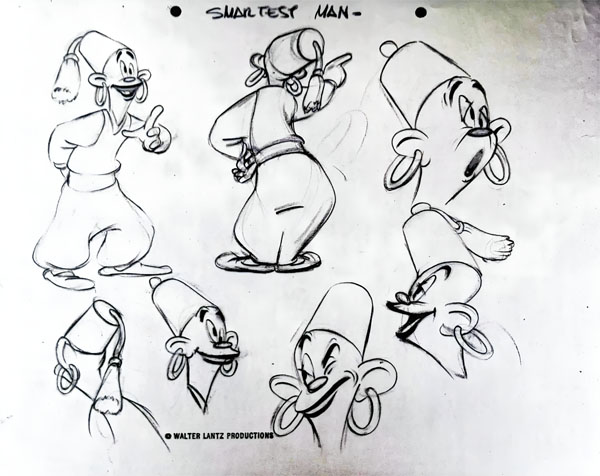

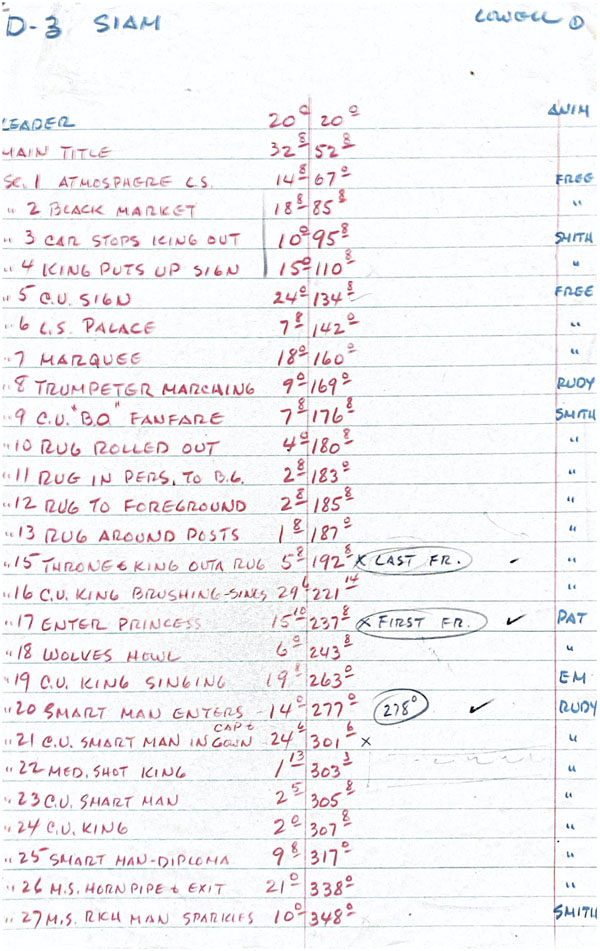

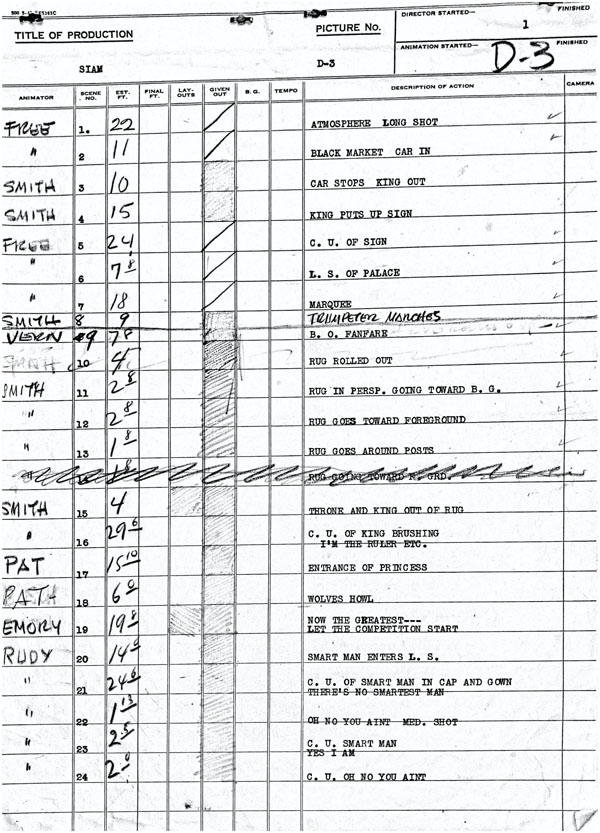

In the cartoon’s storybook premise, the king of Siam (later Thailand) wishes to marry off his daughter and stages a contest whereby the “greatest man” can win her hand. As soon as the competition starts, Porter and Hoefle’s minor-keyed rhythmic tune accompanies the action. For the contest sequences, Culhane cast his animators to fitting “roles.” The entire section of the Smartest Man in Siam—a slobbery dope of a suitor absent in the original song—was handled by Shamus’s old cohort, Rudy Zamora. (Though never credited onscreen at Lantz during this era, production papers reveal that Zamora animated lengthy sequences in Culhane’s Meatless Tuesday and The Barber of Seville.)

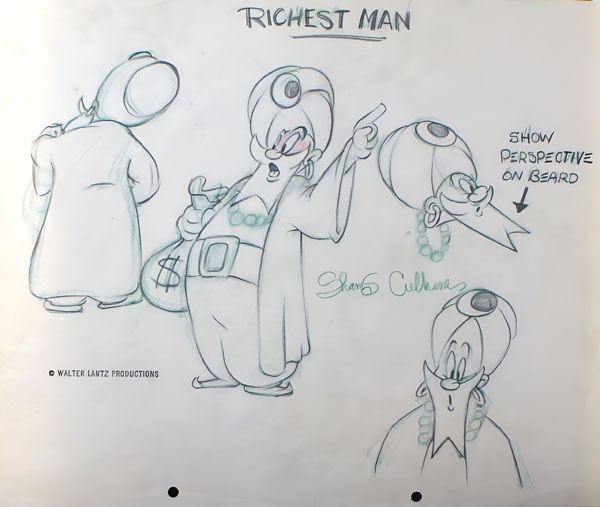

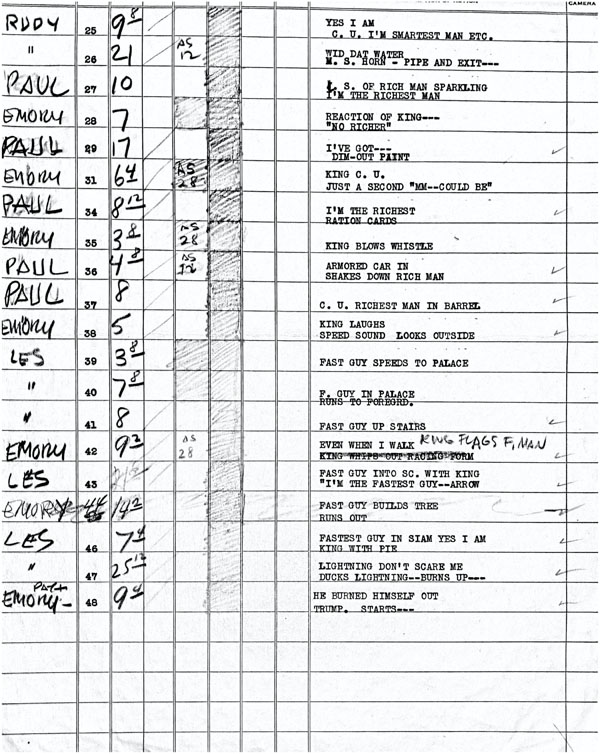

Paul Smith was assigned to the Richest Man in Siam, who flaunts his affluence via large money bags and high-demand items rationed during wartime: sugar, gasoline, rubber tires, red meat, and canned goods.

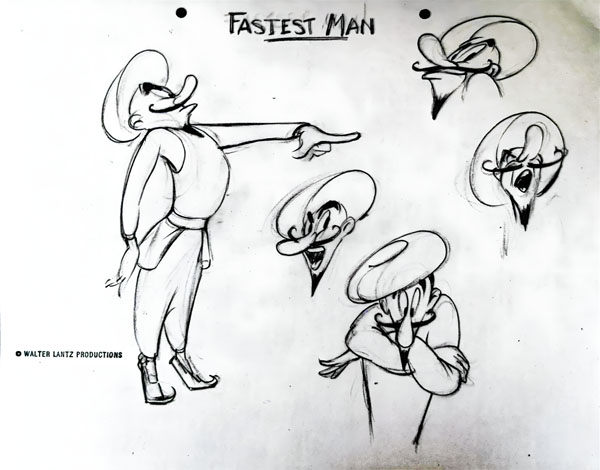

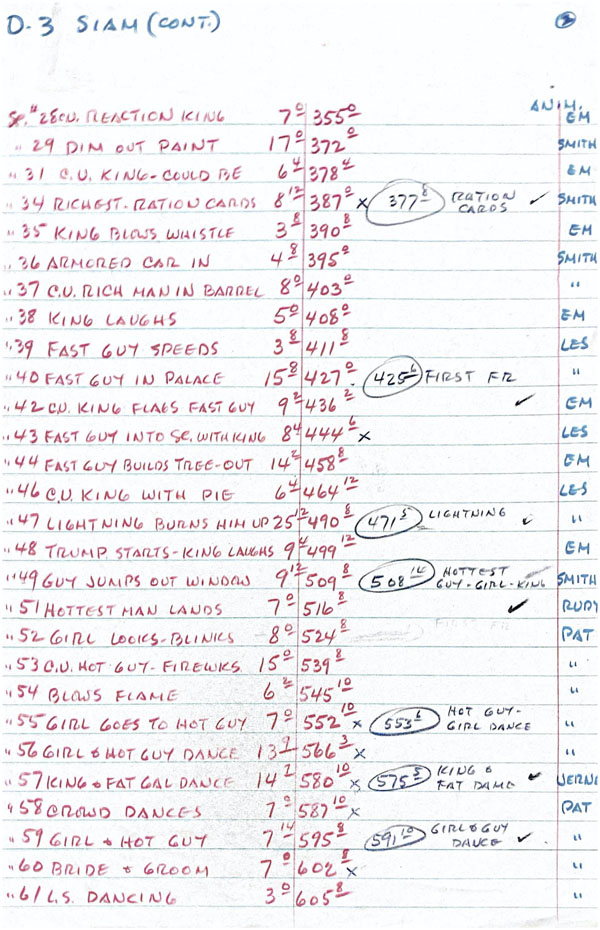

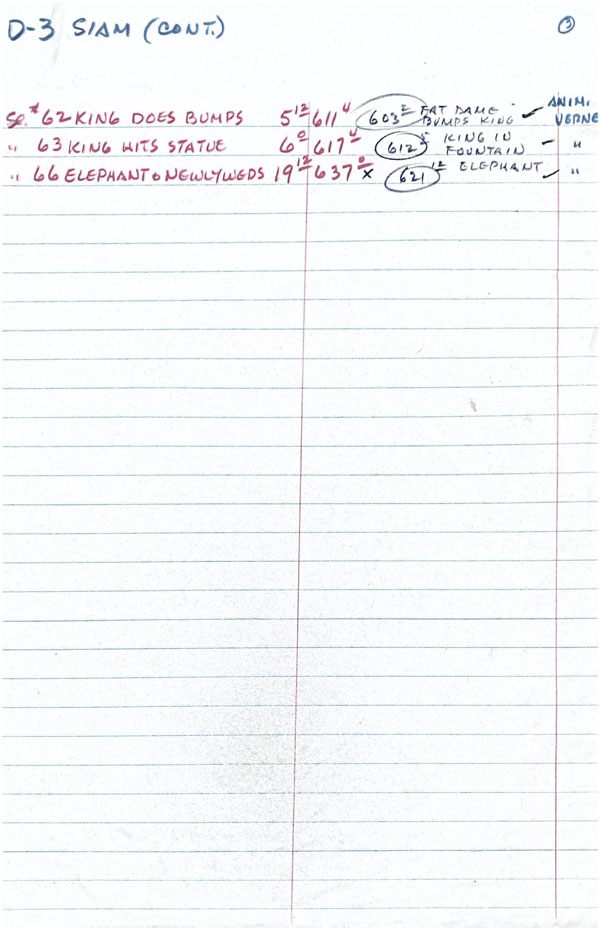

Lantz mainstay Les Kline was given The Fastest Man in Siam, with Emery Hawkins’ work shoehorned in between. Kline animated the Fastest Man’s accelerated entrance into the palace, then his skid to a stop before shooting an arrow into the air. (In another innovative move, the Fastest Man’s outlines are inked in white, which gives his movements a visual flair.) Hawkins’ animation steps in when the Fastest Man zips to the other side of the frame, grows an apple tree, and plucks an apple to place atop his head directly in the arrow’s path. Kline’s work returns when the suitor dodges lightning, takes a bow, and then is struck by a single bolt of lightning. (In its release, a Showmen’s Trade Review write-up mentioned The Strongest Man in Siam, who doesn’t appear in the cartoon.)

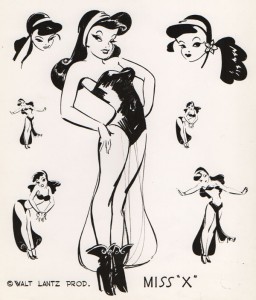

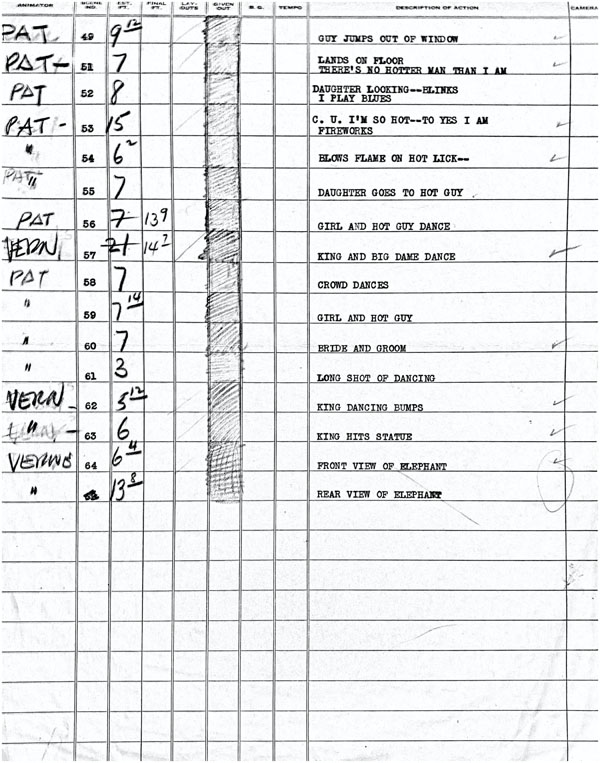

John Richard (Pat) Matthews, a former Disney and Screen Gems artist, was tasked with the cartoon’s plum role: the character designer and chief animator of the king’s daughter. Tex Avery’s MGM cartoon Red Hot Riding Hood, an outstanding sensation in its day, was pivotal for its realistic depiction of the alluring nightclub songstress who drove the Wolf into a licentious frenzy. Siam reflected Tex Avery’s outward influence in scene 18, also credited to Matthews, when the king’s subjects morph into howling wolves over the shapely princess.

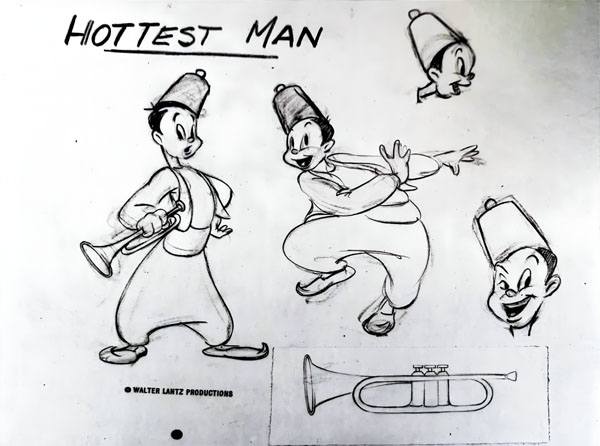

Hottest Man in Siam model sheet, photo caption: This early model sheet was drawn before the Hottest Man in Siam was modified in the final film. As it stands, the Hottest Man bears a resemblance to Private Snafu, which Art Heinemann also designed.

After the Fastest Man in Siam is snuffed out like a burnt match, the king and his daughter hear lively jazz trumpeting from above. Its sounds originate from The Hottest Man in Siam, a much younger suitor than the others. The Hottest Man’s mellow vocals captivate the princess, and the two lock eyes in mutual attraction. Temperatures rise as hot jazz releases flames from the solid sender’s trumpet. The two cavort in a Lindy Hop dance. Matthews’ scenes in Siam radiate sexual magnetism. (Two production drafts for Siam survive; both credit different animators for the Hottest Man’s jump from the palace window in scene 49. One draft credits Paul Smith while another tags Pat Matthews. Upon closer inspection, the drawing and timing resemble Emery Hawkins’s work.)

After the Fastest Man in Siam is snuffed out like a burnt match, the king and his daughter hear lively jazz trumpeting from above. Its sounds originate from The Hottest Man in Siam, a much younger suitor than the others. The Hottest Man’s mellow vocals captivate the princess, and the two lock eyes in mutual attraction. Temperatures rise as hot jazz releases flames from the solid sender’s trumpet. The two cavort in a Lindy Hop dance. Matthews’ scenes in Siam radiate sexual magnetism. (Two production drafts for Siam survive; both credit different animators for the Hottest Man’s jump from the palace window in scene 49. One draft credits Paul Smith while another tags Pat Matthews. Upon closer inspection, the drawing and timing resemble Emery Hawkins’s work.)

Like other cartoon producers, Lantz saw the pop culture impact of Red Hot Riding Hood and wanted to get in on the action. The Princess of Siam’s realistic look deviated from standard cartoon animal characters and was a challenge animator Matthews accepted with zeal. Lantz and Culhane encouraged Matthews to create a human figure akin to the pin-up illustrations ogled by soldiers abroad. Walter admitted to the press that her looks were modeled after Hedy Lamarr, Betty Grable, and Lana Turner.

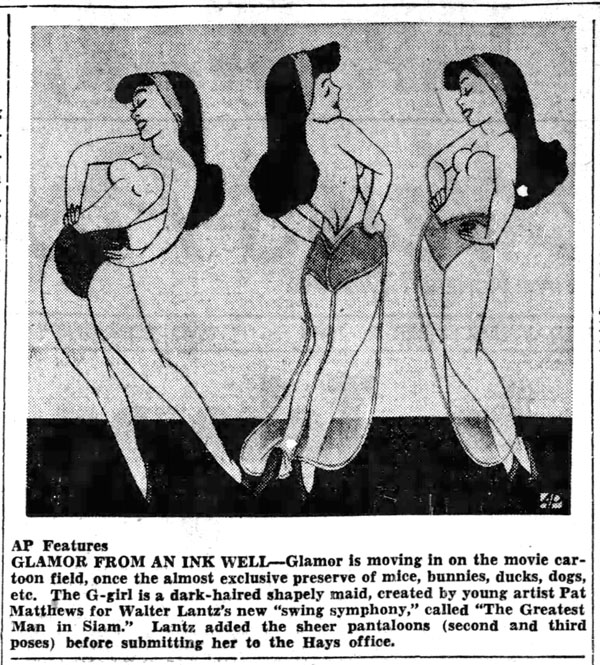

By November 1943, Siam’s pencil animation was completed. Before its final release to theaters, production faced a blowback—the Hays Office objected to the Princess’ bare, voluptuous legs. All her scenes were redrawn with a pair of translucent pants; this pleased the censors.

Monrovia News Post (Dec. 2, 1943)

“Recapturing a dance is an animator’s weakness from an artistic and creative point of view,” said an article in The Hollywood Reporter’s November 3, 1943 issue, which detailed Siam’s production. Preston Blair, the artist responsible for Red Hot Riding Hood, animated Red’s movements without the basis of live-action. In Siam’s case, Lantz and Culhane relied on Universal’s film vaults, which contained the phenomenal swing dancing of Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers in the 1941 musical comedy Hellzapoppin’. This use of live-action reference, publicized in The Hollywood Reporter, involved marking frames of key dancing positions on the film print. From a rear projector, the key frames were traced from the film image beamed on the animator’s drawing board. After the key frames were traced, it was up to Pat Matthews to bridge the dance steps with his work for a more natural movement.

The earliest known record of Siam’s theatrical exhibition was at the Ritz Theater in Alva, Oklahoma, on January 3, 1944. Weeks later, a reporter’s droll comment in the January 22 edition of Showmen’s Trade Review read: “The King’s daughter has been drawn very realistically in her harem costume, which means a blindfold should be put over little Johnny’s eyes when she appears.” Siam opened in New York on January 25 at Broadway’s Criterion Theater, billed with Universal’s latest war film, Gung Ho! On March 27, Culhane’s Swing Symphony had its general release to theaters nationwide.

Shamus Culhane and Walter Lantz

During the post-war years, Castle Films secured the rights to Lantz’s cartoons and selected a handful for the non-theatrical home movie market, with Siam among the titles. In 1949, Castle struck reels of small-gauge Technicolor prints to sell in camera stores and film rental houses. When Siam was reissued to theaters on September 11, 1950, Boxoffice magazine recognized the cartoon’s topical humor: “This is heavily larded with World War II gags that may have been funny five years ago.” Among the surfeit of wartime references in the cartoon: King Size, as the sultan is labeled in the cartoon, plays on the wartime trend of “king size” cigarettes; the signage on the promotional marquee outside the king’s palace promotes a skirmish between Lockheed’s aircraft employees vs. the shipbuilders from Kaiser Shipyards; the Smartest Man is characterized as a draft dodger that winds up caught by a volunteer and removed from the premises to join the Navy (due to his “water on the knee”); an air raid warden zips onto the scene to spray dim-out paint on the Richest Man’s blinding jewelry, which suggests that Siam enforced blackouts.

In production materials and publicity, Siam’s glamour gal was temporarily known as “Miss X,” which was too suggestive for the censors. Since Lantz planned to feature her in another Swing Symphony, Abou Ben Boogie, he had to choose a different name. Walter proposed a nationwide contest for exhibitors and moviegoers to name his new female sensation, offering the victor a $100 War Bond. Five thousand suggestions were submitted to Lantz and his fellow judges. Eleanor Lukofsky, a Scranton theater exhibitor, won the award for her suggestion, “Miss XTC.”

Thanks to UCLA Special Collections for the production materials. Additional thanks to Frank M. Young for peer review and copy-editing, and Keith Scott, Tom Samuels, Vincent Alexander, and Yowp for production notes.