Gene Kelly’s World of Animation

Among the gallery of greats who have appeared on the screen with animated characters, there is something unique about Gene Kelly. His talents as a director, choreographer, producer, and especially dancer, he was uniquely suited to the art of combining live action with animation.

Gene Kelly (right) and director George Sidney discuss “Anchors Aweigh”.

Kelly’s frequent collaborator and future director Stanley Donen came up with the idea to put Kelly into an animated sequence for 1945’s Anchors Aweigh. Kelly loved the idea, and so did Walt Disney. He met with Walt to discuss the possibility of sharing the movie screen with Mickey. Contrary to several accounts, Walt never said anything to the effect of “Mickey will never dance in an MGM picture!” Kelly’s widow, Patricia Ward Kelly, is eager to dispel this myth, among others. Mickey had already appeared in two 1934 MGM musicals, Hollywood Party and Babes in Toyland (1934, which also featured the Three Little Pigs). Walt had a fine relationship with Louis B. Mayer.

The truth is that the Disney studio was pushed to its limits by WWII. Many artists and staff members were overseas. The studio was producing more material to support the war effort against the Axis than any other in Hollywood, and as usual, Walt the perfectionist was exceeding the budgets provided by Washington. His brother Roy was reticent to commit to the Kelly project or any other outside endeavors, as the studio was under severe strain.

Walt told Kelly that he would intercede with Mayer if there was any resistance to creating the sequence at the MGM Animation studio. Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera’s unit was devoted almost exclusively to the popular, acclaimed, and profitable Tom and Jerry cartoons, so if there was any resistance, it would have had to come from producer Fred Quimby, because working on the Kelly project would reduce the time on T&J shorts.

Walt told Kelly that he would intercede with Mayer if there was any resistance to creating the sequence at the MGM Animation studio. Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera’s unit was devoted almost exclusively to the popular, acclaimed, and profitable Tom and Jerry cartoons, so if there was any resistance, it would have had to come from producer Fred Quimby, because working on the Kelly project would reduce the time on T&J shorts.

It is also possible that Ub Iwerks’ recently developed optical printer system was put to use in the Kelly sequence. Though I am unable to fully confirm this, it makes sense as to the timing of the production and the seamlessness of the final result.

For those unfamiliar with how it was done, here is a fascinating video by Bill Martin of the Academy Special Effects branch:

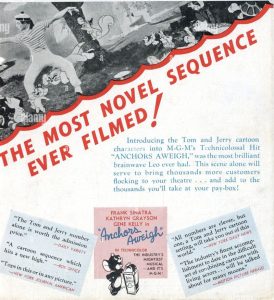

“The King Who Couldn’t Dance” sequence in MGM’s Anchors Aweigh is widely considered to be one of the most effective combinations of live action and animation ever created. Kelly’s athletic, precise dynamics allowed an enormous amount of interaction with Jerry. It was a perfect storm of animation talent during the heyday of theatrical cartoons. Among the finest artists in the business were involved, many of them who would work for Bill and Joe for decades.

The partnership between Kelly, Hanna, and Barbera connected them to Anchors Aweigh director George Sidney, whose next move was to include an animation/live-action sequence in Dangerous When Wet, in which the duo swam through adventure with Esther Williams. Sidney’s Holiday in Mexico had a prologue animated by the H & B unit.

“Invitation To The Dance”

Kelly, Hanna, Barbera, and their team tried to do things with the technique in “Sinbad” that never been attempted before, including camera moves and perspectives that were sometimes too ambitious for the capabilities of the mixed media. Most famous is the snake dance that was modeled by legendary dancer Carol Haney. There is little question that those in the industry, particularly animation, took note of this sequence, identifying what worked best, like keeping the camera locked down for the most part, and keeping direct human-cartoon contact fast and minimal.

George Sidney and his father, MGM exec Louis K. Sidney, became instrumental in helping Hanna and Barbera get into trailers and other animation, teetering on the edge of television, including the original I Love Lucy titles. When Hanna-Barbera Productions began in 1957, Sidney was the third partner. Sidney and his home studio, Columbia, helped get H-B animation and product placement into his 1963 film version of Bye Bye Birdie, and bring such stars as Ann-Margret and Tony Curtis to guest star on The Flintstones.

“Jack and The Beanstalk”

The results were varied. Once again, the team reached extremely high, with lots of impressive set pieces making the most of the technique. But as the money ran out, Hanna-Barbera had to rely on effects contractors who were not always up to the task. Kelly was not pleased at first, but had to understand that this was no longer MGM at the pinnacle of time, detail, and budgets. The night before the special aired, he hosted a birthday tribute to his friend Jackie Gleason on rival network CBS, and Gleason mentioned Jack and the Beanstalk at the end of the show. Promoting programming on another network was rare in those days.

Warner Archive released the special on DVD. A few musical highlights can be previewed here:

The special, which aired on Sunday night in place of The Wonderful World of Disney, won an Emmy, garnered high ratings, and received good reviews. It convinced NBC to greenlight Hanna-Barbera’s 1968 series, The New Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, TV’s first weekly live-action/animated series.

Ten years after Beanstalk, Gene Kelly was one of the celebrity hosts of Yabba-Dabba-Doo! The Happy World of Hanna-Barbera, a two-hour clip fest in the manner of That’s Entertainment. In 1974, when Kelly and Fred Astaire starred in That’s Entertainment, Part 2, Hanna-Barbera provided an animated sequence featuring rotoscoped images of MGM stars.

But it was all started by a mouse. And a sailor man. Jerry and Gene.

“The King Who Couldn’t Dance”

As noted in this keen book about Hanna-Barbera, the Columbia book and record set with Gene Kelly telling and singing the animated story from Anchors Aweigh was the first recording featuring characters created by Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera. Its producer, Hecky Krasnow, moved from Columbia to the newer Colpix label, where he was responsible for the first LP with Hanna-Barbera stars, Ruff and Reddy: Adventures in Space.